The Hebron Historical Society

Hebron, Connecticut

Enjoy Hebron - It's Here To Stay ™

Hebron has lots of land identified as “Open Space”. These expanses can be found throughout the town. Some areas, such as Gay City, are owned by the State, but many are owned by the Town and are there for all to enjoy. The town-owned Open Spaces are resource protected and for passive recreational use. That means they should remain just as they were when purchased, other than for future trail marking.

Luckily for all of us, some of these spaces were not developable; they were steep, rocky, perhaps a bit wet, and not accessible by roads. They may have been old farms that were split by tracks when the Air Line RR went through. They may have been right next to a body of water where a dam and mill had been located. In whatever manner, the property had been well used and appreciated by our early settlers. When walking through these areas, one can relax, view the natural beauty all around, and imagine how life was lived “back when”. Take a look at the attached Open Space Map and see what’s available for your enjoyment.

In 1811, as can be found on a map, Hebron had many streams but very few roads. In its early days, Hebron made much use of its “brooks”. Over 30 historic water-powered mill sites have been found on Fawn and Raymond Brooks, the Blackledge and Jeremy Rivers, the water that flowed from Amston Lake (originally “North Pond”), and more. Take a walk in one of these public areas, and YOU, too, can discover an old mill site.

The Raymond Brook Preserve has a very interesting history. The area could be known as Settlers Park since Hebron’s first settler, William Shipman, from Saybrook, built his cabin there in 1704. The Shipman family was a direct recipient of land from the Will of Attawanhood, Sachem of the Western Nehantics. The Raymond Brook Preserve’s West, North and East boundaries follow, respectively, Church Street, Kinney Road, and Millstream Road with a connection from Millstream across to Holy Family Church.

In 1790 John Gilbert, who had previously acquired the settler’s property and more, sold his 144.5 acres to Erastus Perkins, who sold that same property in 1804 to Hebron’s Zechariah Cone. For $3,870, Cone then sold the 144.5 acres to Ira Bissell in 1839. The North part of the house, presently owned by the church, was already there when the Bissells acquired it. The Bissell family lived on and improved the property until 1914 when they sold some acreage to the Hildings, and the remaining 50 acres were bought by the Hortons in 1920. Interestingly, the corner lot at Church Street and Kinney Road had a “dwelling house” when it was bought by John Gilbert prior to 1786. The well from that early house remains today and serves the later 1850’s home on Kinney Road.

Frederic Phelps Bissell, who lived on the above property his entire life, kept journals from 1847-1905. From those journals, one can learn all about life in Hebron in the mid-19th century. F.P. Bissell comments on his daily and seasonal farm activities, his connection with St. Peter’s Church as Warden and Caretaker, his shingle, sorghum, and sawmills, participation in local politics and his time in Hartford as Hebron’s representative, the daily weather, as well as illnesses, deaths, and marriages of townspeople, and much more. A narrative written from the journals can be found on the Hebron Historical Society website (hebronhistoricalsociety.org) along with a larger map of Hebron’s “Open Space”, and also the town’s Water-Powered Mills map.

Exploring Hebron’s Open Space is a “Buy 1, Get 2 Free Deal”. You provide the energy for the walk and are rewarded with views of Hebron’s natural beauty as well as learning more about the Town’s History.

Known in Washington, D.C. as the “Angel of Mercy”, Josephine Sophia White was born in the Hope Valley section of Hebron in 1814. She was a descendant of Peregrine White, the first white child born in New England. Education was obviously important to the White family as Josephine attended both the Burrows Hill School and Bacon Academy. She married Charles S. Griffing in 1835, and the couple had five daughters, three of whom survived to adulthood.

By 1842, the couple had relocated to Ohio, undoubtedly due to that state’s passion for social reform that matched their own. The couple quickly became involved in abolition efforts. The Griffing’s home was a station on the Underground Railroad. Josephine gave lectures for the Western Anti-Slavery Society and wrote for The Anti-Slavery Bugle. To encourage a larger crowd, and to make her message more palatable, Josephine had her younger sister present a musical program.

During the Civil War, Josephine had moved to Washington where she assisted the newly-freed slaves in learning a new life of self-support. Josephine established connections with people in the federal government as well as many aid organizations. She found food, clothing, and housing for the massive number that arrived in the city. Griffing was even given the use of barracks for housing the destitute. Josephine herself helped find northern homes for more than 7,500 freed people, and often rode with them on the train to get them settled.

Josephine opened Industrial Schools for freedwomen to learn “marketable” skills such as sewing. In Griffing’s own words, "the Industrial School furnishes an opportunity for instruction in social science, and domestic relations, as well as the higher forms of Industry, and a marked change is observable in personal tidiness, good manners, and in the control and government of young children - whom some of the mothers are obliged to bring with them to the Rooms." But it was not enough.

To gain further support for needs of the newly freed slaves, Josephine lobbied members of Congress for more aid. The outgrowth of her efforts was the formation of the Freedmen’s Bureau. She received backing from President Lincoln, Secretary of War Stanton, and many of the conservative congressmen. She also received support of many governors as she traveled about. Similar to many politically-controlled groups, there was major disagreement regarding methods to achieving goals. The Freedmen’s Bureau was discontinued at the end of 1869 although much need still existed.

Following her years of work for the Freedmen, Josephine resumed her efforts towards Suffrage. Josephine wrote to Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1870 and said “we must lay a corner stone, make Congress understand that the women of the country will be heard.” And she further stated, “O! how I see the want of regulation in national affairs, that can never be accomplished, while Govmt. is administered on the male basis of Representation.” Unfortunately, she only lived a couple more years before dying of Consumption (or T.B. as it is known today).

Upon her death in 1872, Josephine’s body was returned to Hebron, and is buried in the Burrows Hill Cemetery. She was perhaps the bravest crusader ever to be born in our community. Her life’s work is well summarized on the small cemetery monument marking her final location: “A friend to the slave, the poor and oppressed. With unswerving faith in God's eternal justice, her life was given in their service.” To read more about Josephine Griffing, select Hebron & Slavery on our menu. The site includes many documents about Josephine and her work with Abolition, Reconstruction and Women’s Suffrage. Josephine was but one of Hebron’s many special residents.

MaryAnn Foote

Women’s History Month – March 2021

“The Gilead Room” as it now appears in the Yale University Art Gallery

“The Gilead Room” as it now appears in the Yale University Art Gallery

By Mary Ann Foote

Since the Yale University Art Gallery’s reopening on 12/12/12, a “Gilead Room” has been included as part of the newly expanded and renovated galleries. How did a room from Gilead find its way to Yale? When did it “go to Yale”? How old is it? What is its story?

In about 1930, the CT Society of Colonial Dames of America were surveying still extant 17th to early 19th century structures. When Colonial Dame member, Mrs. Holcombe, saw the parlor of the Gilead house, she shared her find with J. Frederick Kelly, a New Haven architect. Following Mr. Kelly’s visit to the house, he immediately contacted Everett Meeks, the dean of Yale’s School of Fine Arts. Mr. Meeks then wrote to Mr. Francis Garvan, a generous supporter of fine arts, about “the finest Connecticut room I know of.” Mr. Garvan accepted all appraisals of merit regarding the room; negotiations were held with J. Kellogg and Ethel White; and for $5,000.00 the woodwork from the parlor now belonged to Yale. More than one recent owner of the Gilead house has offered to buy back the elements of the parlor!

J. Frederick Kelly and his brother Henry immediately initiated the plans for removing the woodwork. Extensive drawings were made of every elevation in the room. A numbering system was placed on each piece of wood with detailed direction as to how it fit with its neighbor. Photographs were taken while the room was intact, and those pictures also showed the numbers on each piece. The reader will note that the Gilead Room today exactly matches its photograph taken prior to dismantling.

Elevation of North Wall as drawn and identified by J. Frederick Kelly in 1930

Elevation of North Wall as drawn and identified by J. Frederick Kelly in 1930

1930 photo of North Wall, marked for dismantling and easy reassembling, by New Haven architect, J. Frederick Kelly

1930 photo of North Wall, marked for dismantling and easy reassembling, by New Haven architect, J. Frederick Kelly

The plan was for Yale to immediately install the room in their Department of Fine Arts gallery. It would have been quite simple to dismantle and move the room, and then re-install it at Yale with the Kelly brothers’ instructions. However, the fiscal difficulties of that era prevented the plan from moving forward. The woodwork was, instead, put into storage where it was out of sight for over 75 years. When Hebron’s Olive (White) Doubleday was told of the plan for the conservation and reinstallation of her childhood parlor, she simply said, “It’s about time!” Unfortunately, Olive is no longer here to see it, but she was very excited to know it was finally going to happen.

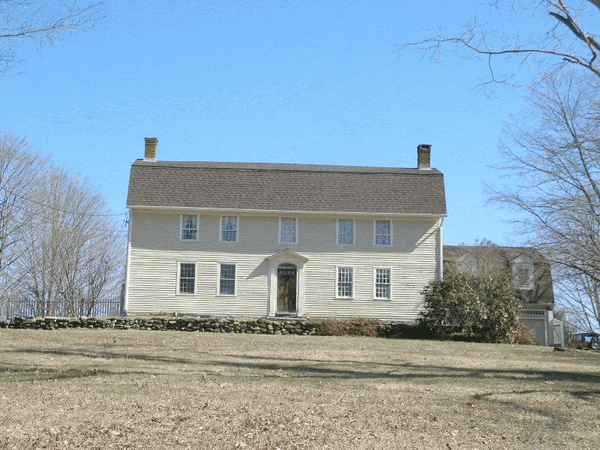

Where in Gilead was this room located? While driving through the village, have you ever noticed an unusually proportioned old house? It is very tall, has 3 floors, yet the main portion is extremely shallow from front to back. As soon as you see the picture of the house, you’ll say, “I know that house; I always look at it. I wonder how old it is?” The house is located south of Meetinghouse Road on Gilead Street, Route 85, and can be seen by either looking across a cornfield or from Gilead Street. The different views will show the uncommon shape.

The parlor was removed from the lower left room at 650 Gilead Street

The parlor was removed from the lower left room at 650 Gilead Street

Credit: Lara Bordick, 2008

The house as it looked in 1930, photo by J. Frederick Kelly

The house as it looked in 1930, photo by J. Frederick Kelly

The house has been referred to as the Youngs’ house, the Ellis Luther house, the Rowley house, but this writer suggests it could also be called the “Curtice House”. Between land records and probate distributions, researching a property history is often confusing. With a lack of complete records, first resolving the age of a structure through modern methods could help determine the ownership at time of home construction. Let’s follow the primitive path.

Joshua, son of Uncas, Sachem of the Mohegan Indians dictated his will in 1676, and left land rights to men from the Hartford, Saybrook and Windsor settlements. Taking advantage of this land, a man named Joseph Youngs from Southold, Long Island in 1702 purchased a “1000 acre right” from John Parker, one of the Saybrook Legatees. A bit later, the land right was converted to “solid ground”, and Joseph Youngs became one of Hebron’s earliest settlers. His “100 acer home lott” was laid out in Gilead on May 5th, 1713, and the property record for Lot # 52 can be found in volume 1 of the Hebron Land Records.

The 1744 map of Hebron shows two homes labeled “Youngs” on Gilead Street, and two more on Wall Street. None of these houses, however, are this “Gilead House” as it wasn’t yet built. Between the years of acquiring the land to the date of the map, Hebron’s Vital Records inform us of Joseph and Margret Youngs’ family. Sons Ephraim and Eliphalet were married in 1733 and 1734, respectively. Other children were Lemuell, Ebenezer, Joseph, Jr., Benaiah and Margrit. Joseph Youngs’ wife, Margret, died in 1758, and Joseph himself in 1768. We can guess that various family members lived in those marked houses during the intervening years?

In 1750 Joseph Youngs divided his Gilead Street property between his sons, Eliphalet and Ephraim. Between the two properties was land Joseph Youngs had previously given to the Society of Gilead for a Meetinghouse. Ephraim was the son with property to the south, and therefore it was his descendants and their relatives who would have built the Gilead House. Although many names are similar, and therefore very confusing, stay with me while we follow the early property history

Ephraim, who died in 1761, and Hannah (Rollo) Youngs had two children, Ephraim, Jr. and Hannah. Daughter Hannah married Abijah Rowley in 1751, but she had already died by 1752. Abijah then married Hannah (Curtice) in 1755. Ephraim, Jr. married Hannah’s sister, Elizabeth (Curtice) in 1757, but Elizabeth was widowed in 1763. Neither Ephraim, Jr. nor his sister Hannah had any offspring, so the property interest moved in the direction of the Curtice connection.

In 1768, two months after the death of family patriarch, Joseph Youngs, Widow Elizabeth (Curtice) Youngs sold a portion of her property to her brother-in-law, Abijah Rowley. Abijah served in the Revolutionary War and died in Vermont in 1776. Abijah’s widow, Hannah (Curtice) sold 40 acres of their property in 1782 to her brother, John Curtice. [Widow Elizabeth died in 1786; Widow Hannah died in 1812.] In 1812 John Curtice sold 16 acres, including house and barn, to Rev. Nathan Gillet, the pastor of the Gilead Church. It was at this time that the property left the Curtice family.

To provide more light on the subject of age, the Yale Conservation staff ran tests, called dendrochronology, on the woodwork. This is a scientific method of dating based on the analysis of patterns of a tree’s growth rings. Those tests showed that the timber had been felled in 1770. The wood would then have gone through a natural air-drying process before it could be utilized. However long the drying took is when the house was built -- or at least when the architectural elements were added to the parlor, if testing wasn’t done on the entire building.

Local lore holds that Ellis Luther built the house. He did own a woodlot for about 10 years; and, when sold, it included a “3 saws mill”. Even more interestingly, however, is that Ellis Luther in 1780 married a Sybil Post whose mother just happened to be Deborah (Curtice), sister of Elizabeth, Hannah and John! If Ellis Luther did build the house, it probably wasn’t until around 1775 since he was born in 1755. If we conjecture a bit, we can surmise that Ellis met Sybil while building the house and married her shortly thereafter!

So--, who built the house and when? Now it’s up to you to continue the research!

Corner Cupboard from Gilead Parlor finally out of Storage

Corner Cupboard from Gilead Parlor finally out of Storage

Back to the ca. 1770 Gilead Room: The room was packed up about 80 years ago, moved to New Haven, and then sat in various, sometimes unsavory storage locations for all those years. If one thinks that the Yale restoration experts simply followed J. Frederick Kelly’s marked photographs and drawings, reassembled the room, and said, “voila, it’s ready to exhibit,” one is mistaken.

Just in the last five years have the components of the parlor found their way back into daylight. Following their removal from storage, the elements were sealed in airless bags so that any insidious bugs, which may have penetrated the wood, would be eliminated. The architectural elements were then cleaned, had paint analyses done, as well as additional research and conservation work. Surprisingly, after all those years in various locations, very few pieces were lost and in need of replication.

Once all conservation work had been completed, it was time to re-assemble the room. Luckily, Yale has a large preservation & conservation facility which provides plenty of space for laying out the components. Following the 1930 J. Frederick and Henry Kelly drawings, photographs and markings, the separate elements were reassembled. The woodwork included a mantel, doorways, wainscoting, the corner cabinet, windows, and trim.

The Gilead room's most spectacular and sought after pieces include the paneled chimney wall, the carved summer beam, and the corner cupboard. To see a time-lapse video of the parlor being reassembled by YUAG conservators, click to watch.

Gilead Room Being Reassembled in YUAG Preservation/Conservation Facility

To see the Gilead Room itself, visit the Yale University Art Gallery at 1111 Chapel Street (at York Street), New Haven. [Unless otherwise noted, all graphics are credited to the American Decorative Arts Department, YUAG.]

Hebron’s loss was the Yale University Art Gallery’s gain, even if it took Yale an awful long time to realize it.

Click on each photo to enlarge.

Photos courtesy of Carolyn Aubin

This January marks the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. To note and celebrate Hebron's important role in the abolition of slavery, the Hebron Historical Society has created a new section, "Hebron & Slavery" on its website. The new section gathers together dozens of documents chronicling Hebron's rich tradition of opposing slavery and supporting human rights. The reader will find enough information with which to write a term paper!

Early citizens of Hebron made statements and took strong action against slavery long before 1863. Hebron was ahead of Prudence Crandall's Canterbury school by nearly 50 years, and promoted abolition 75 years before Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin" was printed. In 2007, Hebron was selected as a site on the Connecticut Freedom Trail, a tribute to our town's citizenry and their great respect for all neighbors, regardless of color or status.

Abduction of the Cesar and Lowis Peters Family

Many have heard about the 1787 abduction of Hebron slaves, Cesar and Lowis Peters, along with their 8 children. Their owner was the Rev. Samuel Peters, a minister of the Anglican Church on Godfrey Hill, Hebron. Due to the Reverend's Loyalist sympathy and sermons to his parishioners, he was threatened with "tarring and feathering" by the town fathers. Rev. Peters fled to England in 1774, leaving his family & slaves to fend for themselves.

In 1787 Rev. Peters was still in England, although he had accrued liability in Hebron, so the men designated by Rev. Peters with power-of-attorney, John and Nathaniel Mann, were attempting to straighten out their relative's financial mess. To pay a debt, Nathaniel Mann arranged to have Cesar and Lowis sold to a South Carolina slave owner. The attempt of one David Prior to retrieve his new slaves is the story of an attempted abduction and the response of Hebron's citizenry to prevent it.

A little chicanery by Hebron's judicial and law enforcement officials stopped Mr. Prior at the dock in Norwich, just prior to loading his "property" and heading south. Not only did Hebron's officials save their friends from an uncertain future, but worked with the state to have Cesar and Lowis emancipated within two years. Various depositions show that Rev. Peters never wanted to do anything but free Cesar and Lowis.

Even after the quick action by Hebron citizens to save the Cesar & Lowis Peters family from being sent to South Carolina, some of Hebron's wealthier landowners continued to hold slaves. The Federal Census of 1790 lists 15 slaves still owned in Hebron -- among the owners, some who fought for the freedom of Cesar and Lowis! By 1848, the State of Connecticut had abolished slavery within its boundaries.

Josephine Sophia (White) Griffing

Not as well known, but equally as important is the abolitionist and freedmen's work of Hebron's daughter, Josephine Sophia (White) Griffing. She was born December 18, 1814 to Joseph and Sophia (Waldo) White, and was a descendant of Peregrine White, first white child born in New England in the Mayflower. Josephine received her early education in the Burrows Hill School and completed her studies at Bacon Academy. In 1842, several years after her marriage to Charles S. Griffing, the couple moved to Ohio.

It was in Ohio that Josephine Griffing's reform work began. Among her acquaintances were: Abraham Lincoln, William Lloyd Garrison, Edwin L. Stanton, and others. Her home was a station on the Underground Railroad, a respite for runaway slaves. She was part of the abolitionist speaking circuit, an unusual deed for a woman, and she received much favorable attention.

Probably the largest contribution of Mrs. Griffing was her work in recognizing and protecting those who had recently been released from slavery. Following their emancipation, the ex-slaves were quite lost when it came to making their own living and caring for their families. Many ended up in camps, still without direction or wherewithal. After the birth of the Freedmen's Bureau, many of our politicians simply lost interest in the cause. The Freedmen's Bureau worked as both "conscience and common-sense of the country". It was here that Josephine aggressively approached government leaders to gain support for our newly freed citizens.

Josephine died in 1872, and is buried with many of her relatives in

Hebron's Burrows Hill Cemetery. Her gravestone reads: "A friend to the slave, The poor and oppressed. With unswerving faith in God's eternal justice. Her life was given in their service."

For More Information

To read the full stories of both the Cesar Peters family and Josephine Griifing, go to the website of the Hebron Historical Society (HHS) at http://www.hebronhistoricalsociety.org and click on Hebron & Slavery. The site includes dozens of original documents, as well as the movie, "Testimonies of a Quiet New England Town," produced by HHS.

To read about Hebron's placement on the Connecticut Freedom Trail, see http://www.ctfreedomtrail.org/.

To study Yale University's "Citizens All: African Americans in Connecticut, 1700-1850", go to http://cmi2.yale.edu/citizens_all/stories/index.html. The Cesar and Lowis Peters story is found in the "Freedom" chapter.

Mary Ann Foote, Hebron Historian

January 2013