The Hebron Historical Society

Hebron, Connecticut

Enjoy Hebron - It's Here To Stay ™

Where I Live – Hebron and Connecticut

A compilation of Local Connections to enhance studies of Connecticut

Using Where I Live by Elizabeth Norman, Melanie Meehan, and Ashley Callan

Connecticut Explored Inc. West Hartford, CT., revised text 2019

By John D. Baron -2023

Directly across from Hebron Elementary School about 1000 feet back from Route 85 is some of the oldest soil in New England. It is made up of crushed stone, soil, and gravel that existed in New England before the last glacier melted. Currently, it is covered by a layer of fertile soil that has built up over the past 10,000 years. This pre-glacial soil now provides moisture for the fertile soil layer above. Originally, this soil deposit was preserved by the last of the glaciers sitting upon it. As a result, the area from Hebron Elementary School to this deposit was where the glacier pushed and dumped larger rocks and gravel. It is not as fertile as further east on the property.

Native Americans, especially after they had started to plant the three sisters (corn, beans, squash), were keen observers of their environment. This is why they seasonally encamped where Hebron Center is now located. This location provided access to low marshy areas just north of Hebron Center rich in naturally occurring food stuffs and the good planting in the area across from Hebron Elementary School.

Early settlers were also aware of this site’s unique fertile quality. They named the flat land that Hebron Center is located on, the Plain of Mamre which was located by the Biblical settlement of Hebron and was linked with the narrative of Abraham.

From the earliest days of settlement, the land across from Hebron Elementary School was owned by prosperous farmers who reaped bounty from the land. Owners like David Barber and Sylvester Gilbert were slave owners. Enslaved individuals were responsible for moving large boulders from the edge of the fertile tract and creating stone lane ways so that crops would not be harmed by herds of farm animals or hay wagons. By the early 1800’s slavery had vanished in Hebron, but wealthy farmers living in the center of town needed farm labor. Most of the land across the street from Hebron Elementary School was then owned by Governor John S. Peters. He employed free African Americans to run his farm. In the early 19th century at least seven formerly enslaved families live in Hebron Center much like their middleclass Yankee neighbors. These families did not own much land, but earned their living by working for wages farming the land owned by Hebron’s wealthiest farmers. This is a very unusual system to have developed. Until 1848 slavery was legal in Connecticut, but Hebron slave owners decided on their own long before 1848 to manumit their slaves. Once free, these skilled African American farmers found steady employment during Hebron’s most prosperous years. At the same time, slavery was expanding in the American South and heading West. With the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, southern slaves were freed, but were re-enslaved by the share cropping system that developed during Reconstruction. This was a very different economic system than what developed in Hebron with wage earning farm laborers.

The land across from Hebron Elementary School is some of the oldest and richest farm land in Hebron. During the Revolutionary War, In the spring of 1781 the French troops stationed in Lebanon left their winter quarters and marched south along what is Route 85 today. This was a fateful military operation, these soldiers recruited from across Europe were part of the last battle of the Revolutionary War – the Battle of Yorktown. From that point forward, the former English Colony of Connecticut would be known as the State of Connecticut and be part of a new nation – the United States of America.

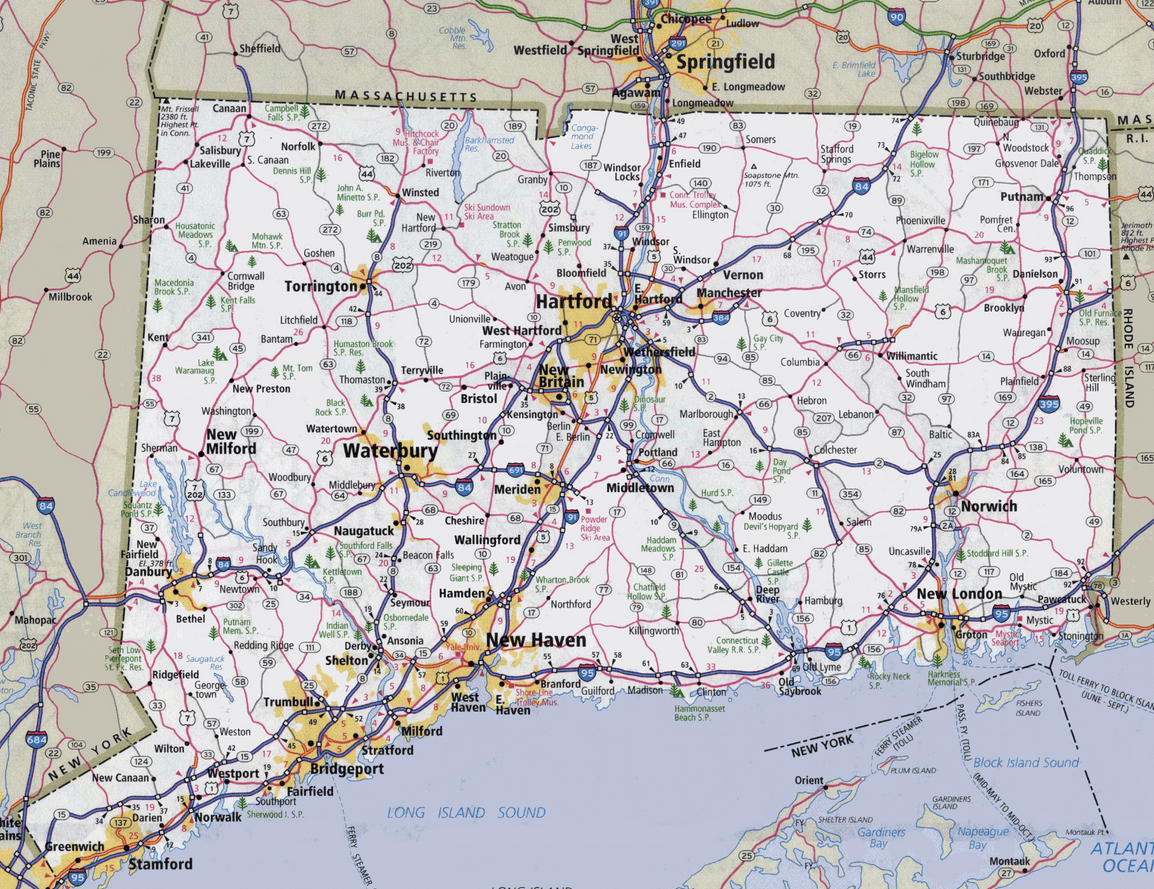

Essential Question – How can people get to Hebron from out of state?

1 plane?

2 train?

3 Bus?

4 Car?

What are the nearest cities to Hebron?

What are the nearest Rivers?

Essential Question -- What role does water play in Hebron?

Is Hebron on any major rivers?

In an age of sailing where would the nearest ports be to Hebron? Before cars, how would goods from ports get to Hebron?

How far is the nearest salt water beach to Hebron?

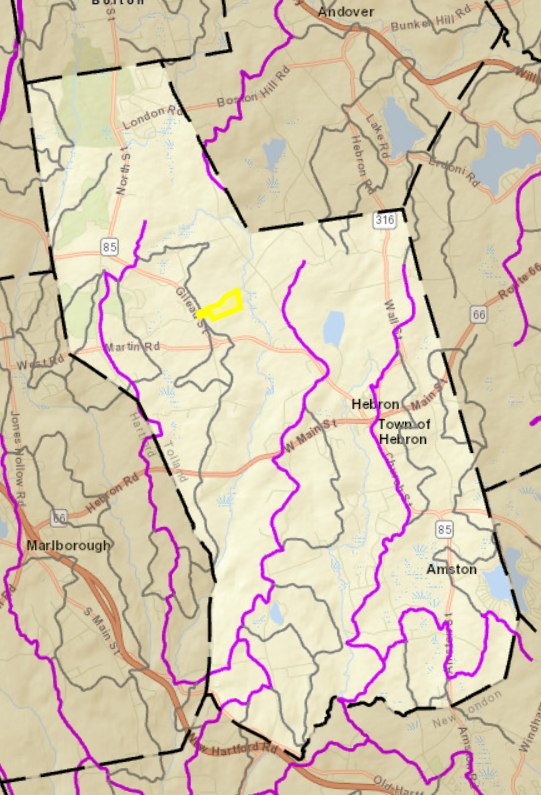

Look at a GIS map of Hebron – does Hebron have any streams, brooks, lakes or ponds? Are there any areas in Hebron where the land is wet, but not considered a stream, brook, lake or pond? If so, why are these areas an important part of the watershed?

GIS maps of Hebron are available at https://www.axisgis.com/hebronct/

Notice on the map above how the brooks and rivers in the northern part of Hebron drain either to the north east or south west. Burnt Hill is at a watershed. Some of the Burnt Hill drains northeast to the Thames River and some its water drains to the southwest and the Connecticut River.

Sharpening your thinking skills

? Do the streams and rivers of Connecticut suggest that the land along the coast is lower than inland? If so, would this difference in height be a good thing or bad thing?

? Native Americans tended to camp by lakes or ponds. Can you think of some reasons why they would do this? Where are there lakes or ponds in Hebron?

* Archaeological and anecdotal evidence indicate that Burnt Hill, Holbrooks pond, and Amston Lake were areas where there were Native American encampments. The earliest evidence of Indigenous people comes from burnt Hill where Paleoindians hunted 10,000 years ago.

The Great Snow of 1717 occurred when Hebron had been incorporated for only 9 years and there were relatively few families living in Hebron. Native Americans remembered the snow that fell that March as greater than anything their ancestors had ever known. Snow started to fall on March 1st with more snow coming in on March 4th and 7th. The snow that accumulated was almost 5 feet high and winds created snow drifts as high as 20 feet as high as a two-story building. Most houses in Hebron were one story high and people found the best way to get out was through their garret windows. Families had to tunnel their way through snow drifts to get to their barns to feed their livestock and to wells to get water and firewood. Snow had to be cleared from chimney tops so that smoke could escape. The Great Snow was hard on native animals. The deep snow prevented deer from grazing during the winter and hindered their ability to run from predators. For several years after 1717, venison on the table was uncommon.

The summer of 1816 was a difficult time for people living in Hebron and New England in general. In March when the winter freeze should have been ending, the ground was still frozen and it snowed. In April the fruit trees, particularly apple trees began to bud out, but a late frost killed them ending hopes for much cider in the fall. On June 7th, some parts of Connecticut received 6 inches of snow! By the Fourth of July temperatures were in the 40’s. On August 22nd there was frost on the ground. Then by August 24th there was a heat wave and rain. This was followed by a frost that killed off the corn before harvesting in September. Most families living in Hebron earned their living from farming. In 1816 they were unable to plant their crops or harvest hay for their animals. The result was that food prices rose for people living in factory villages like Gay City and Hope Valley, as well as people living in cities. In 1816, furniture maker John Graves began to build his house on Church Street across from the Synagogue. The frozen ground would have made digging the cellar difficult. However, with little farm work to tend to, there were plenty of neighbors to help raise the frame. While cold temperatures made heavy work cooler, frost and ice were hazards on ladders and scaffolding in the middle of summer. Paint and plaster could not be applied due to the cold. The summer of 1816 convinced many Connecticut families and some in Hebron to move out west where farm fields had fewer stones and they hoped warmer summers.

On Sunday, March 11, 1888 at about 7 P.M. snow started to fall in New England and continued until Wednesday depositing over 3 feet of snow and creating snow drifts as high as a two-story building. People had to burrow their way to their woodpile, water pump, barn and outhouse. During this time the train through Amston did not run and the telegraph lines were down. A seventeen-year old girl, Susan Pendleton recalled that youngsters made skis out of barrel staves and delivered goods to people who were “shut in” by the storm.

On September 21, 1938 Hebron was in the path of a huge hurricane. Falling trees fell near buildings and upon cars. The wind blew off part of the roof of St. Peters’ Church, the chimney of the old town record building and the entire north side of the Griffing house standing across from the Wall Street Burying Ground. Almost everyone in Hebron was affected. Barns and corn silos were blown away by the storm in an age when most people in town were farmers. For weeks thereafter, local people earning 35-45 cents an hour, cleaned up fallen trees and debris.

Essential question – how does Hebron’s weather compare to other places.

Activity for 2 weeks -- record the day time high for Hebron, New London and Litchfield.

? Which location tends to be warmest?

? Which location tends to be coolest?

? Do you think this pattern would be the same in winter as it is in the fall?

? Why would temperature matter to a farmer raising crops?

? Given what you have discovered and discussed about temperature which would be the best town to have a farm? New London? Hebron? Litchfield?

Reflection—Today working adults tend to leave Hebron each day to go to work. However, families tend to live year-round in Hebron. That’s what a suburb is all about.

Before Europeans arrived the Indigenous people of Connecticut moved with the seasons.

? What benefit to the land might there be to moving each season?

* Native Americans moved with the seasons. Hebron was a summer to fall camping area, but too cold in winter compared to along the coast. Burnt Hill is the highest point in Hebron, it got its name due to Native Americans burning over the undergrowth. At first this was done for hunting purposes to cut down on brambles, but also insects like ticks. When farming was introduced, Burnt Hill was planted with the three sisters (corn, beans, squash) and after harvesting the field stubble was burned. Since the fire could be seen from a distance, Burnt Hill was also an area where different clans met seasonally to trade copper and stone for projectile points and to arrange marriages and other social institutions. Archaeological evidence indicates Burnt Hill has been frequented by humans from about 9-10,000 years ago, some 3500 years before the Great Pyramids were built!

Podcast on teaching about Indigenous People

Hebron’s Indigenous Past Background information by Sarah Sportman, Connecticut State Archaeologist, David Leslie PhD, and Sarah Holmes PhD.

Paleoindian Period (12,500-9,500 BP)

In the Northeast, the Paleoindian Period dates from 12,500 to 9,500 BP, during the final glacial period. This was a time marked by a return to severe glacial conditions (McWeeney 1999). The earliest archaeological evidence for human occupation in the New England region dates to approximately 12,500 BP (Singer 2017). The archaeological record reflects a settlement system based primarily on small, highly mobile social groups seasonally dispersed in search of resources. The diet consisted of a wide range of food sources, including small and large game, fish, wild plant foods, and perhaps currently extinct megafauna (Meltzer 1988; Jones 1998). Caribou likely played a significant, if seasonal, role in subsistence. However, small game, fish, fowl, reptiles and wetland tubers were also important components of the diet at this time.

Paleoindian Period land use patterns and subsistence activities in the Northeast are relatively scarce (Spiess, Wilson and Bradley 1998). Few intact Paleoindian sites have been found in Connecticut. To date, five sites have been investigated and published in detail: Upwards of 50 fluted points have been recovered as isolated finds across Connecticut. The scarcity of identified sites in the region indicates that population density was likely very low at this time. The small size of sites dating to this period, and the high degree of landscape disturbance over the past 12,500 years, also contributes to poor site visibility overall.

Late Paleoindian point from Burnt Hill, Hebron, CT. Note that the material for making this spear point came from the Hudson River Valley and might have reached Hebron through an early Indigenous trade route.

Archaic Period (9,500-2,700 BP)

The Archaic Period dates from 9,500 to 2,700 BP in the Northeast and is characterized by generalist hunter-gatherer populations utilizing a variety of seasonally available resources. The period is subdivided into the Early, Middle, Late and Terminal Archaic Periods on the basis of associated changes in environment, projectile point styles and inferred adaptations (Snow 1980; McBride 1984). Artifacts dating to the Middle and Late Archaic Period have been identified within a mile radius of Hebron Elementary School and on Burnt Hill in Hebron.

Each subperiod is discussed below.

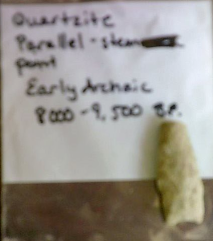

The Early Archaic Period (9,500-8,000 BP) Probable time Burnt Hill is first occupied

Pollen evidence indicates a gradual trend toward a warmer climate beginning around 10,000 BP (McWeeney 1999). By this time Pleistocene megafauna had disappeared and given way to modern game species such as moose, muskrat and beaver. It is feasible deer was not abundant until the end of this period when oak began to dominate upland forests. Plant and animal resources became more predictable and abundant as the climate stabilized, permitting Early Archaic populations to utilize a wider range of seasonal resources. Population density remained low during this period as reflected in the sparse representation of Early Archaic sites in the regional archeological record. This low representation could be due to changing environmental conditions deeply burying, inundating or destroying many early sites through erosion, or due to the difficulty of recognizing Early Archaic assemblages (Funk 1997, Jones 1998). Stone tool assemblages dating to the Early Archaic period have been recovered from several sites in the Northeast and indicate this period can be characterized by a numberof distinct episodes. The most poorly understood period between 9,500 and 9,000 BP A quartz lithic industry in which projectile points are extremely rare occurs locally between roughly 9,000 and 8,500 BP

Early Archaic point from Burnt Hill, Hebron, CT.

The Middle Archaic Period (8,000-6,000 BP)

Pollen evidence indicates a trend toward a warmer, drier climate during the Middle Archaic Period, as well as the development of alluvial terraces along Connecticut's major river systems (Jones 1999). Most modern nut tree species established themselves during this period providing a new food resource for human foragers and many game animals including deer, turkey and bear. Evidence of Middle Archaic Period occupation in Connecticut is more widely documented than for the preceding periods and indicates specialized seasonal activity in different resource zones during a period of population increase (McBride 1984; Jones 1999). The development of grooved axes suggests the increased importance of wood being used as a raw material, while the presence of pebble net sinkers on some regional sites implies a growing reliance on marine and riverine resources (Dincauze 1976; Snow 1980).

The settlement patterns are oriented, at least seasonally, toward large upland interior wetlands (McBride 1984; Jones 1999). The data suggest seasonal re-use of such locales over a long period of time. Coastal and riverine sites may be poorly documented because of rising sea levels that resulted in deep alluvial burial.

Middle Archaic points from Burnt Hill, Hebron, CT.

Late Archaic Period (6,000-3,700 BP)

The Late Archaic Period in the Northeast is characterized by an essentially modern distribution of plant and animal populations. This period is considered a time of cultural fluorescence reflected in evidence of burial ritual, population increase, and long-distance exchange networks (Ritchie 1994; Dincauze 1975; Snow 1980; Cassedy 1999). The Late Archaic Period is one of the best-known temporal sequences in southern New England. During most of this period, large revisited seasonal settlements are located in riverine areas and along large wetland terraces, while smaller more temporary and special purpose sites are situated in the interior and uplands (Ritchie 1969a and b, McBride 1984; Cassedy 1997, 1999). The nature and distribution of sites suggest aggregation during summer months, with seasonal dispersal into smaller groups during the cold weather (McBride and Dewar 1981).

Late Archaic points from burnt Hill, Hebron, CT.

Terminal Archaic Period (3,700-3,000 BP)

A transition in settlement and subsistence patterning began to occur with the onset of the Susquehanna Tradition, also referred to as the Terminal Archaic Period (Dincauze 1975). A number of technological innovations appear as well. These include the use of steatite bowls and the rare manufacture of cord-marked and grit-tempered ceramics. Lithic assemblages contain high proportions of chert and other non-local lithics such as argillite, rhyolite and felsite. Regionally available quartzite was commonly used as well, but the use of local quartz became uncommon at this time. Settlement focused on upper river terraces rather than floodplains as well as expansive lacustrine and wetland settings (McBride and Dewar 1981). The interior and uplands were used less extensively (McBride 1984). Human cremation burials were common at this time (Dincauze 1968; Robinson 1996; Leveillee 1999). These changes in technology, lithic material preference and settlement organization may represent the arrival of non-regional peoples or ideas rather than in situ developments, though the debate over the possibility of migration remains active (Robinson 1996).

Terminal Archaic points from Burnt Hill, Hebron, CT

The Woodland Period (2,700-450 BP)

The Woodland Period is characterized by the increased use of clay pottery, celts and non-local raw materials as well as the introduction of bow and arrow technology, smoking pipes and horticulture (Lavin 1984, Feder 1984, 1999). An increase in site size and complexity along with greater sedentism and social complexity was likely the result of an increase in population, particularly at the end of this period (McBride and Dewar 1987; Lavin 1988). The Woodland Period is traditionally subdivided into Early, Middle, and Late periods based on ceramic styles, settlement and subsistence patterns, as well as political and social developments (Ritchie 1969a & b; Snow 1980; Lavin 1984). Despite these changes, most recent scholars see the Woodland Period as a continuation of the traditions and lifeways of the preceding Archaic Period (Feder 1984, 1999).

The Early Woodland Period (2,700-2,000 BP)

Early Woodland regional complexes are generally characterized by stemmed, tapered and rare side-notched point forms; thick, grit-tempered, cord-marked ceramics; tubular pipe-stones; burial ritual; and suggestions of long-distance trade and exchange networks (Lavin 1984; Juli 1999). The Early Woodland Period remains poorly understood, and is less well represented in the archaeological record than the preceding phases of the Late Archaic. This may be the result of shifts in settlement that promoted the formation of larger, but fewer seasonal aggregation camps. It is possible that incipient horticulture focused on native plant species (George 1997). The existence of stone pipes suggests the trade of tobacco into the region by this time.

Early Woodland point from Burnt Hill, Hebron, CY.

The Middle Woodland Period (2,000-1,200 BP)

The Middle Woodland Period is characterized by increased ceramic diversity in both style and form, continued examples of long-distance exchange, and at its end the introduction of tropical cultigens (Dragoo 1976; Snow 1980; Juli 1999). Much of our current knowledge of the Middle Woodland Period in southern New England is from work done by Ritchie (1994) in New York State. Ritchie noted an increased use of plant foods such as goosefoot (Chenopodium sp.), which he suggested had a substantial impact upon social and settlement patterns. Ritchie further noted an increased frequency and size of storage facilities during the Middle Woodland Period, which may reflect a growing trend toward sedentism (Ritchie 1994; Snow 1980). At this time jasper tool preforms imported from eastern Pennsylvania are entering the region through broad exchange networks (Luedtke 1987).

Settlement patterns in Connecticut indicate an increased frequency of large sites

adjacent to tidal marshes and wetlands along the Connecticut River, a decrease in large upland occupations, and a corresponding increase in upland temporary camps (McBride 1984). The tidal marshes supported a wide variety of terrestrial and aquatic animal and plant resources, allowing for longer residential stays (McBride 1984).

Pottery from Amston Lake may date from the Middle Woodland Period.

Late Woodland Period (1,200-450 BP)

The Late Woodland Period is characterized by the increasing and intensive use of maize, beans, and squash and changes in ceramic technology, form, style, and function. Settlement patterns reflect population aggregation in villages along coastal and riverine locales and the eventual establishment of year-round villages. However, the use of the upland-interior areas by small, domestic units or organized task groups on a temporary and short-term basis remains apparent as does this trend toward fewer and larger villages near coasts and rivers. It has been hypothesized that these changes can be attributed to the introduction of maize, beans, and squash, but it is unclear how important cultigens were to the aboriginal diet of southern New England groups, especially those with access to coastal resources (Ritchie 1994; Ceci 1980; McBride 1984; McBride and Dewar 1987; Bendremer and Dewar 1993; Chilton 1999). Although sites clearly demonstrate the use of tropical cultigens in the Connecticut River Valley, wild plant and animal resources were still a primary component of the aboriginal diet. The use of imported chert increases over time in the Connecticut River Valley implying social, economic, and/or political ties to the Hudson Valley region. Ceramic style affinities also suggest western ties at the end of this period (Feder 1999). Activities associated with a more sedentary subsistence pattern, such as the cultivation of maize, beans, and squash, resulted in the development of a more complex social organization. Regional variation between various tribal entities is reflected in stylistic design elements found on pottery in particular. Prior to this time, the populations were fairly mobile, loosely based kin-groups that required little, if any, form of centralized authoritative power. Leadership roles were determined on a case-by-case basis and often shifted according to circumstance. This began to change with increasing sedentism.

Points from Burnt Hill Hebron, CT. At this time there is a local tradition of a seasonal encampment site in Hebron Center where a community grinding stone or quern was located. There may also have been another encampment site close to Amston Lake.

Contact Period Overview

The Seasonal Round

Although the European trading networks impacted the daily lives of Indigenous peoples throughout southern New England, they continued to practice many of their traditional subsistence strategies. Archaeological sites in coastal and inland locations throughout Connecticut reflect a series of occupations taking place within specific resource rich areas on an annual and seasonal basis. Communities settled closer to the coastline and riverbanks to fish and gather mollusks in the spring, summer, and autumn months. Large amounts of shell found along the coastline of Connecticut attest to these activities taking place. For riverine settings there is evidence of ancient fishing weirs and intensive horticulture.

In addition to attracting wildlife, wetlands and marshland provided raw materials such as rushes, cattails and other fibrous plants for making basketry and matting. By mid- April many groups cultivated maize, beans, squash, and tobacco in the fields adjacent to their settlements. Like their neighbors to the south, many communities in the Connecticut River Valley adopted maize horticulture early on and foodstuffs were considered an integral part of trading networks in the area. Local plants were collected, such as nuts, berries, herbs, and tubers. In the colder months, provisions cached away from summer habitations were utilized. As the winter months approached, family groups or bands on the immediate coast removed further inland to wooded areas where archaeological sites reflect the presence of smaller temporary hunting camps.

In contrast to the end of the Late Woodland, after European contact, cultural rather than environmental factors influenced the subsistence patterns of local Indigenous peoples (Ceci 1979). The impact from European trading networks, Native wampum production and the fur trade disrupted the balance of power in the years just prior to the Pequot War in 1637 (McBride 1994:44). After contact, European trade affected Indigenous populations who opted to shift their settlements to one geographical area to intercept and negotiate with their trading partners. This was certainly the case for inland groups along the Connecticut River and other tributaries including those within Hebron. The same applied to coastal dwelling peoples who constructed fortified villages for protection while vying for trade (Ceci 1979). Fortifications were often occupied on a continual basis for at least a segment of the population, possibly housing the sachem’s family. However, other horticultural activities took place within close proximity to these structures.

At the time of European contact, the socio/political organization of Indigenous

communities living in coastal and inland areas of southern New England was becoming more highly stratified. In the larger village sites, the demographic included extended families whose sachem was a close family relation. In the 17th century, it is important to note, infectious disease introduced by the European voyagers and fishermen decimated local Indigenous communities and disrupted traditional leadership roles observed just after contact that were often matrilineal.

Gun flints found at Burnt Hill, Hebron, CT. During the 18th century with the introduction of African American slaves, Hebron became a tri racial community.

Historic Period - Hebron

The lands within modern day Hebron were granted by Attawanwood (Joshua), son to the Mohegan Sachem Uncas, in his will dating to 1676 to Thomas Buckingham, William Shipman and many others referred to as the ‘Saybrook legatees” (Trumbull 1797) . In the17th century, the territory in the upper Connecticut River Valley was the aboriginal homeland of the Podunk, Tunis, Poquonnoc, Wangunk and Sicoags and further north of Bolton, the Nipmuc Wabaquasett. In 1637, prior to the English attack on the Pequot fort

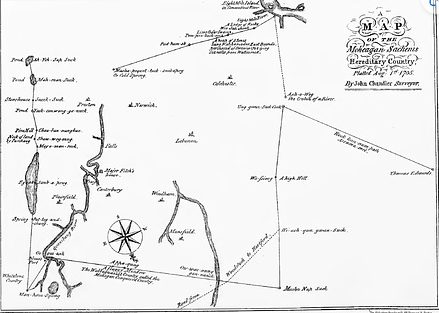

in Mystic, these communities coalesced along the river and paid tribute to the Pequot who controlled trade along the Connecticut River. After the Pequot War, the Mohegan claimed the territory up to the southern border of the Nipmuc Wabaquasett as part of their hereditary right and the Wabaquassett lands through conquest. This issue came to light as a result of the controversy with Owaneco and Samuel Mason over lands transferred to Connecticut. John Chandler’s 1705 survey of Mohegan lands was used as evidence in the complaints by the Mohegan over the loss of their land rights. Hebron’s town bounds were encompassed within Chandler’s survey where the previous year Connecticut’s General Assembly granted several colonists the right to settle on the land. (Trumbull)

John Chandler’s 1705 Map of Connecticut with north at the bottom. The marking on the left translated as “A high hill” may represent Burnt Hill .

Question – Of the 6 known Paleolithic sites in Connecticut which is the closest?

* 10,000 years ago, the glaciers had melted and high mountains like Burnt Hill had been carved down to hills. The melting glaciers left behind two long flat plains in Hebron. One is located where Hebron Center and Hebron Elementary School are located and named the Plain of Mamre by early settlers. The other begins above Holbrook’s Pond and runs north to Burnt Hill. This flat area was named the Plain of Abraham.

When the glaciers began to melt, grass, low wind ravaged trees and shrubs began to grow in valleys. This provided mastodons and caribou with food. There wasn’t an abundance of plants to eat, so Paleoindians subsisted on a meat diet using spears to hunt. The tip of the spear would often be made of stone with the edges chipped off to provide a sharp edge. Native People would trade stone that was not local to Hebron. The only metal Indigenous people had was from the copper outcroppings in Granby, Connecticut.

Activity -- Draw a picture of what Hebron might have looked like with low trees, shrubs, and grass on which mastodons and caribou lived with patches of snow and meltwater.

Hands on activity – stone tools were made from knapping or chipping away the edges of stone like flint. Flint knaps a lot like glass leaving behind sharp edges. Students can simulate knapping by using a “Sugar Daddy” on a stick that has been frozen overnight and with round stones from the Dollar Store. They can slowly chip away the edges and form a spear head. Have students think about how Indigenous people would attach this “stone” to a wooden shaft. Since a “Sugar Daddy” is peanut oil free, most students are able to eat the remains eroding the sharp edges of their spear point with their tongues!

Eventually, the climate warmed and fir then deciduous trees dominated the landscape. During the Archaic and Woodland periods, Indigenous people came to hunt in Hebron at Burnt Hill, Hebron Center, and Amston Lake. Woodland animals like deer and rabbits replaced the caribou. Deer could not easily be hunted with a spear. The invention of the bow and arrow made it easier to shoot these animals from a distance. Nets could be used to catch fish in the water and animals on the land.

Hands on Activity—buy a couple of spools of twine from the Dollar Store and cut the twine into 3- foot lengths. Have students work in groups to make nets. It will become very clear to students that working with textiles requires a subset of skills which some have mastered, but not all.

* New England’s Indigenous people were masterful at using materials from their environment to meet their needs. It might be worthwhile to review the concept of needs and wants. Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs and Steel makes the case that there were no wild animals in North America that could be tamed as beasts of burden. Although horses originated in the America’s, they died out long before Europeans arrived. Indigenous People on the American Great Plains reestablished herds of horses brought across the Atlantic by Europeans. There were no American animals that could be milked like cows. Actually, the only animals Indigenous Americans shared with Europeans was the dog. Dogs and humans made a very effective combination of skills and one of the America’s first invasive species. It might be worthwhile for students to make a list of things dogs can do that humans can’t and vice versa.

Humans with stone tools and dogs were able to

* Create shelter from cutting down small saplings and bending them into a dome shape using cedar bark to tie the pieces together. Cattails could be loosely woven together and covered with sections of bark to form a weather tight home with a center fire vented by a smoke hole in the center.

* Create clothing from animal skins. Indigenous people in New England did not weave cloth, but used the hides of the animals they hunted for clothing. Cattail fluff, milkweed or moss could be used for making moccasins warmer or as diapers in a sling around a mother’s shoulders.

* Food was available through sporadic hunting usually by men, but consistently by women using nets and gathering food like cattail roots, sunflowers, and nuts.

Simple hands-on activity – buy some unshelled sunflower seeds (check first to make sure no one is allergic). Give each student a small handful and then when you say “Go” have them shell the seeds using only their fingers for 5 minutes. When the time is up, see who would be the survivors with the most sunflower “meats”

* It was only 1,000 years ago that due to an increase in population Indigenous People turned to farming which had developed in the Middle East 8,500 years earlier. This is an important fact -different cultures use the environment differently. Another factor that Jared Diamond makes is that Europe and Asia are in the same latitude, the Americas are not and Indigenous women had to gather seeds from cold hardy plants over generations for corn from Central America to reach New England. Key Point – Native American women were the first biogenetic scientist! As a result of this genetic process, Indigenous women also gained a knowledge of medicinal plants. Except for hunting which was primarily a male activity (but not exclusively), Indigenous women were the sustainers of their culture and were often elevated to leadership roles in sharp contrast to 17th century English society!

Hands on activity – plant a three sisters garden plot in your classroom and watch it grow throughout the year. If you use heirloom seeds, you might want to share the seeds from your experiment with students in the spring, so that they can go home and start their own three sisters’ garden and at the same time do something good for the environment.

Another activity might involve preserving corn, beans and pumpkin by drying in the classroom. Roasting pumpkin seeds on a cookie sheet in an oven can be a nutritious snack (as long as no one is allergic). Indigenous people did not use a lot of salt because it was difficult to transport. Have students try the seeds without salt and then with salt and decide which tastes better. Early Europeans commented on how healthy and strong Indigenous people were. Part of this is due to their diet which to modern taste was lacking in salt and sugar! We are indeed what we eat.

Hebron Connection -- European contact benefited and disrupted Indigenous people in Connecticut. Trade and an interchange of technology were benefits. Disease and English concepts of land ownership were detrimental. Conflict in Connecticut occurred shortly after settlement with the Pequot War. Forty years later the decimation of the Nipmuc and Wampanoag resulted from King Phillip’s War, one of the bloodiest wars in American history. Even Native Americans who sided with the English like the Mohegan were forced to give up their lands. In 1676 at the end of King Phillip’s War, Mohegan and Western Niantic Sachem Attawanhood or Joshua was forced to sign over the land that would become Hebron on his deathbed. Indigenous people would continue to plant on Burnt Hill and appear in the town records until the 1840’s. However, they were legally defined as second class citizens and not allowed to vote – a situation that would only be changed in 1924!

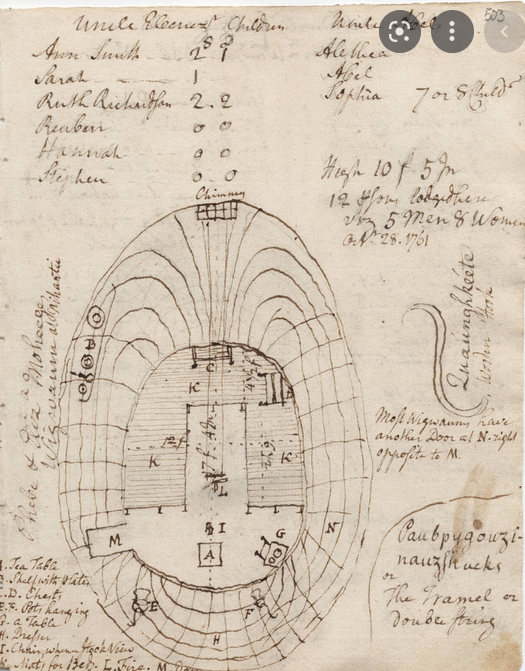

English culture changed Native American culture. Ezra Stiles, the president of Yale, drew the following diagram of a furnished Western Niantic wetu in 1761. This sort of wetu or wigwam would be familiar to early Hebron settlers. Early settlers in Gilead could see Indigenous wetus around the Gilead Congregational Church. Indigenous people continued to plant in areas like Burnt Hill until almost the Revolutionary War!

In the fall of 1761, Ezra Stiles visited the Western Niantic Indian community in the Niantic-East Lyme, Connecticut area. Of the several Indian dwellings or wigwams standing there, he made sketches of two in particular, that of George Waukeets and Phoebe and Eliza Moheage. Both residences are representative of East Coast Algonquian Native architecture – a structure made with a bent-sapling frame covered with reed mats, tree bark, or animal skins.

The Mohegans’ wigwam was a little over ten feet high and could accommodate about a dozen individuals. It contained a raised platform inside, providing space for bedding and other furniture. By the mid-eighteenth century, familiar household items included colonial-styled tea tables, chests, tables, chairs, and dressers. Heat came from a fire pit hearth placed in the center of the earthen floor. Larger wigwams, such as those owned by tribal leaders, had several hearths. Pots made from earthenware or iron hung over the fire from hooks (quaúnghkéete in the Niantic-Mohegan language) that could be adjusted by moveable devices or trammels (paubpygouzinauzshacks)

Hebron Connection—English settlers brought English ideas of individual land ownership with them to Connecticut. Land was not free, but had to be purchased. It is thought that the first Euro-American to ever visit the area that would become Hebron, camped out at the top of Raymond Hill located on Route 85 between Old Colchester Road and Route 207, about a mile south of Hebron Elementary School.. The land on which Hebron is located passed from Indigenous ownership when in 1676, Attawanhood, ( also called Joshua) wrote his will and gave the land to a group of men living in Saybrook, Connecticut. These men known as the Saybrook Legatees or Hebron Proprietors owned all of Hebron. In 1702 they divided the land into 86 home lots, meadow lots, and 100 acre lots. They drew lots and traded land amongst themselves, then started to sell land in Hebron to settlers. People first came to Hebron to settle and live in 1704-1705. William Shipman and Timothy Phelps were two of the first settlers to arrive. They began to build houses and clear fields by where the Church of the Holy Family is now located. They had left their wives and children in Windsor about 20 miles away and had come on foot to Hebron. When they did not return to Windsor on schedule, the Shipman and Phelps families in Windsor began to worry and the wives and children set out to find the men. All went well until they got to Hebron and lost their way. The women stopped at a large rock by where Burrows Hill Road is today. An old Hebron legend records that since night was falling, Mrs. Shipman and Phelps climbed up on the rock and started to call for help. Their husbands heard them and found their way to Burrows Hill where the families were reunited.

Discussion point – Do you think William Shipman and Timothy Phelps’ wives made the right decision to go out to find their husbands?

? Do you think William Shipman and Timothy Phelps were happy to see their family or angry?

Historical Footnote – From 1702-1713 England was at war with the French settlements in Canada. The cause of the war was that the French and their Native

American allies were attacking New England Settlements, burning them to the ground and taking hostages back to Canada. In 1704 /05 when Martha Crow Phelps and Mrs. Shipman set out from Windsor even though the Connecticut Assembly had forbidden settlers in Colchester and other frontier towns from leaving and abandoning a claim to the territory. Thus, the trip from Windsor was more perilous than it might at first seem.

By 1708, Hebron had nine families living in town. Land was set aside for a Green or Common and plans were made to hire a Congregational minister, build a meeting house and parsonage. On May 13, 1708, the General Assembly of Connecticut granted Hebron the privilege of being a town. From that time forward Hebron could legally elect town officials like selectmen and levy taxes. Hebron, Connecticut was established 75 years after the first settlement in Connecticut and 88 years after the Pilgrims came to Plymouth Rock.

Activity – Who are you Gonna call?

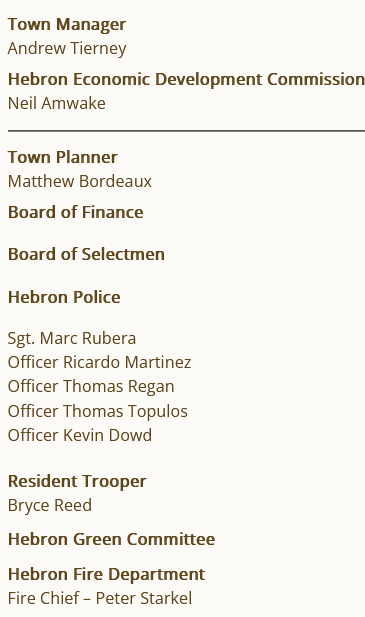

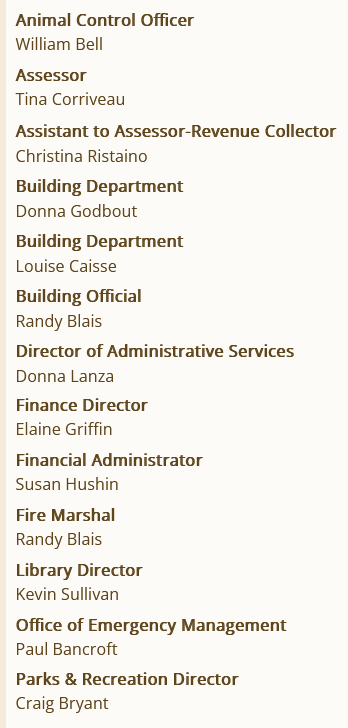

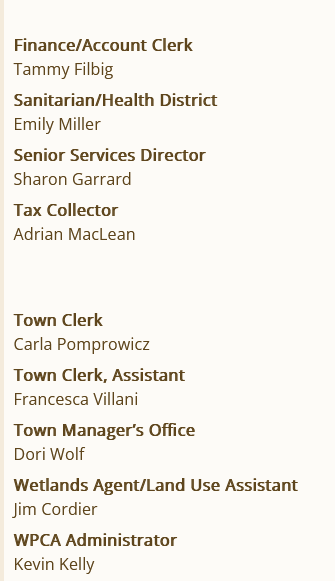

Since incorporation in 1708 Hebron Town Government has provided many services for people who live in Hebron.

Make a copy of the Hebron Town Directory or put it up on the Smart Board. Then ask who you would call for the following problems:

1 Someone broke into a storage shed on your property.

2 You want to put an addition onto your house.

3 Your tax bill seems too high.

4 The town road you live on needs to be plowed.

5 Your neighbor’s septic tank is overflowing into your yard.

6 Your grandmother needs transportation to a doctor’s appointment.

7 There’s a raccoon living under your porch.

8 You need a new dog license.

9 Your neighbor is filling in a swamp.

10 You want to find a book on the history of Hebron

Hebron Town Directory –2022

You might want to discuss with your students that some of the above jobs are salaried jobs and some positions are elected.

Activity How does government pay for the services it provides?

The Three levels of government in Hebron.

Discussion question –Why does a dollar toy at Dollar Tree cost $1.06 at the checkout?

Where does this tax money go--- to the town where the store is located, the state of Connecticut, or the United States government in Washington D.C.?

Property taxes provide money for towns.

Federal income tax provides money for the US government

Connecticut income tax provides money for the state of Connecticut

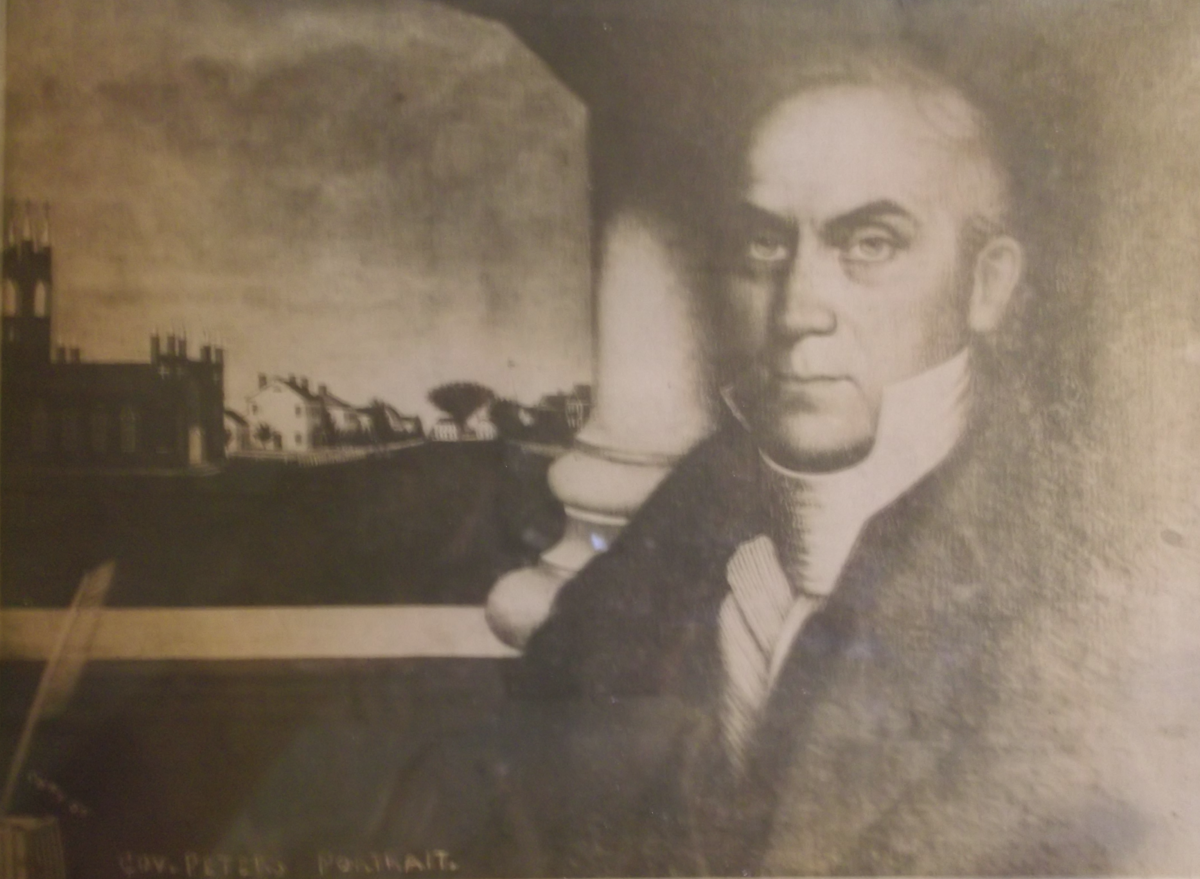

A historic detour -- Did you know Hebron had one citizen who became Governor of the state of Connecticut?

John Samuel Peters was born in September of 1772 on a farm next to Burnt Hill Park. He was named for his grandfather John Peters who first brought his family to Hebron in 1727 and for his uncle, the Reverend Samuel Peters, vicar of St. Peters’ church in Hebron. The Revolutionary War started just 3 years after John S. Peters was born. His father Bemslee Peters supported the English side and spent most of war in England. As a result, John S. Peters’ family was relatively poor, even so, John S. Peters attended school on East Street and then taught school to earn a living. In 1790 he apprenticed for 6 months with Doctor Benjamin Rush of Marbletown, New York. He then studied with Doctor Abner Mosley of Glastonbury. In 1796, he attended medical lectures in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1797, the last year of George Washington’s presidency, John S. Peters began to practice medicine in Hebron and did so for the next 40 years.

In 1806, John S. Peters built a stylish brick house for himself that still stands on Church Street next to St. Peters Church. In 1816 he added a small addition or ell to the house to serve as his medical office. John S Peters was chosen by Hebron voters to be Town Clerk several times and Judge of Probate. In 1810, 1816 and 1817 John S. Peters was voted to represent Hebron in Connecticut’s House of Representatives. In 1818 and 1823 he was elected as a Connecticut Senator. In 1827 John S. Peters became Lieutenant Governor of Connecticut and was elected Governor of Connecticut in 1831 and 1832. Governor Peters was a forward looking individual. Three years after the first train was invented, he urged the General Assembly in Hartford to invest in railroads, turnpikes and canals. John S. Peters also thought fostering industry was equally important. He personally invested in mills in Hebron in the Hope Valley area. John S. Peters felt that education was a first priority in government. When he was young, he taught district school in Hebron. As governor he tried to increase funding and reform for education.

Governor John S. Peters was also interested in preserving the past. He was vice president of the Connecticut Historical Society which now preserves a portrait of the governor and documents related to him.

During his term as Governor of Connecticut, a woman named Prudence Crandall opened up a school for African American girls in Canterbury, Connecticut. Prudence Crandall is Connecicut’s state heroine, but unfortunately her school didn’t operate for long and was closed down by the protest of her neighbors. Governor Peters also tried to increase manufacturing in Connecticut and tried to improve education in Connecticut.

One day when he was governor and traveling from Hartford to Hebron by stage coach, the coach passed an old African American woman carrying a large bundle. Governor Peters knocked on thecoach roof for the driver to stop. Although the driver was annoyed at loosing time, he did so and Governor Peters opened the coach door saying “Hop right in Lyddie and ride to Hebron”. The woman was Lydia Peters a descendant of slaves that John S. Peters’ uncle Reverend Samuel Peters owned before the Revolutionary War

After being governor of Connecticut, John S. Peters returned to Hebron to practice medicine. He often treated Native Americans and African Americans and if they were poor would not charge them. John S. Peters never married. He ran a large farm with the paid help of the African American Peters and Barber families proving the labor. Hebron Elementary School stands on part of his farm land. John S. Peters died in 1858 at the age of 86. There’s a large monument to him in St. Peters’ church yard.

Another notable Hebron Politician -- Sylvester Gilbert tells his own story

Sylvester Gilbert from Hebron Bicentennial Book 1908

Autobiography of Sylvester Gilbert

I was born in Gilead Society October 20th, 1759, in the house built by my father. My father, Samuel Gilbert, was the son of Samuel Gilbert of Hebron, who came from Massachusetts, and his parents from England,

My Mother’s name was Abigail, daughter of Mr. Samuel Rowley of Hebron, the first schoolmaster I ever knew. She was my father’s 2nd wife and died very suddenly when I was about 9 years old. I remember some of her kind attentions to me with gratitude. I was in early youth very feeble, but through the goodness of God have lived beyond the years of all my brothers and sisters, of whom I was the youngest but one, I had three own brothers and two sisters –I was 83 years old the 20th of October 1838, and as now, this 12th day of January 1839, commencing this biographical sketch.

My affectionate and most dearly beloved wife died on the 14th day of May, 1838, age 81 years, one month and 13 days, a blessed partner and companion, with whom I lived 63 years. She was the daughter of David Barber, Esq., merchant, late of Hebron, deceased.

I was educated at Dartmouth College and graduated in August, 1775, married very young, studied law under the tuition of the late Judge Root, then of Hartford. I was admitted to the Bar in Hartford County in November, 1777. The country then being in an arduous and distressing war with Great Britain, – My law practice was small until 1779 when it began to increase, and at the close of the war became extensive.

In 1786 the County of Tolland was established, and I was appointed State’s attorney for the county In the year 1787 (I was elected as) Town continued to be annually elected to that office, except one year, for a term of 23 years, Previously and subsequently I served the Town and Society in sundry other offices, especially as Town Agent and Selectman, many years.

In September, 1780, one month before I was 25 years old, I was chosen Representative to the Assembly. I was the youngest that had ever been elected in Hebron and was the youngest member of the House. Between this time and October, 1812, I was elected a member 30 times, and attended as many sessions of the Legislature and two special sessions. In May, 1826 for last time, I was chosen and attended as a member and formed the house, being the oldest in membership as I was at first the youngest in years I held the office of Attorney from the State till May, 1807, being 51 years, when I was appointed Chief Judge of the County Court and Judge of probate, which offices I afterwards accepted and in which I continued till 1825, when I arrived to 70 years of age

I did not intend this writing beyond one sheet, but cannot do justice to you or myself without an addition. From the commencement of my law practice till 1810 (I had at this time one or two and sometimes three law students in my office). I commenced a thorough review of the law and spent all the time not otherwise necessarily engaged for two years in preparing lectures for a regular law school, and in 1810 began to read lectures to my pupils and continued this business about seven years, having generally from six to ten students in my office

In the year 1800 I built the house we now dwell in, and in the year 1828 took down my old patrimonial house, and gave the site to the Congregational Society in Hebron on which to erect a meeting house where it now stands. My dear and only wife has borne 13 living children, of which number 5 were born deaf, unless Samuel, the oldest, lost his hearing as we supposed by canker and rash, which reduced him near to death, before he was one year old. Our children were, Samuel, Abigail, Theordora, Sophia, Arathusa, Sylvester, Patience, William Pitt, Lewis, Ralph, Clarissa, Mary and Abigail Eliz. Samuel, William Pitt, Lewis, Clarissa and May are my 5 unfortunates, who in childhood required and received an enduring and constant watchfulness and care of a kind and indulgent mother. We were never able to discover any cause of their deafness except the first.

Hebron, Jan. 18th, 1837

Sylvester Gilbert

In 1708 when Hebron became a town, there were nine families living in the entire town.

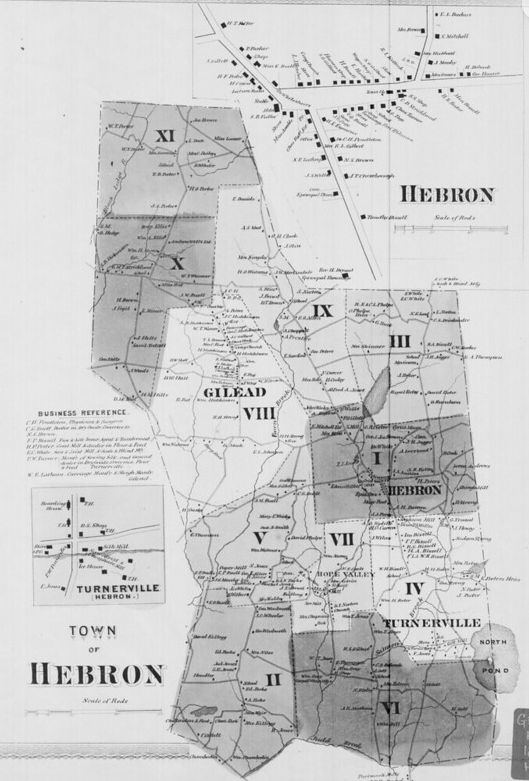

By 1744, Hebron had grown substantially. How many families / houses can you count of the 1744 map? Almost all of these families were farmers. That’s why there were people living all over town, rather than in one place.

In 1822 the Reverend Samuel Peters wrote about farming in Hebron

“They export much produce yearly and many horses, fat cattle, sheep, and swine to the West Indies and drive many to Boston and New York.”

Raising crops in Hebron was not easy. The first settlers cut down trees to create fields. At first, these fields were fertile and produced big crops, but without the tree roots to hold the soil in place, the wind and water eroded the good soil. By the time of the American Revolution, Hebron fields were no longer producing big crops and without the soil, stones appeared. Farmers either built stone walls or moved to areas with richer soil like Vermont and New York. Some farmers bought slaves to remove the stones, plant and harvest the crops. In 1774, Hebron had 52 slaves living in town. Although Connecticut would not abolish slavery until 1848, by the year 1800, there were only 4 enslaved individuals in Hebron and by 1810, slavery was a thing of the past. Many former enslaved people sold their labor to wealthy Hebron farmers. In 1800, Hebron was the wealthiest town in Tolland County and had one the counties highest number of free African Americans living in it. Over time farming changed from raising livestock for meat to producing dairy items like milk and eggs. Many immigrants from southern and central Europe came to Hebron to farm. Farming remained the most common job in Hebron until about 1960. Today there are few farmers, but many stones walls.

Why is Hebron a town, but Gilead isn’t?

Settlement in Hebron was a real estate investment, not a religious one. In order to become a town, a settlement had to have a meetinghouse and settled Congregational minister, since church and state were not separated. The location of the meetinghouse became a major issue in Hebron, because that is where the major roads of Hebron would meet. This meant that it was easier for farms along the major roads to transport extra farm goods for sale. For 8 years after incorporation, Hebron citizens argued about where to build the meetinghouse.

Finally, representatives from Connecticut’s General Assembly placed the location approximately where the traffic light on Route 85 and Route 66 cross. Members of the town planted four acres of wheat to induce a minister to their town and in 1715 Rev. John Bliss answered the call. He was ordained in 1717. Although a meetinghouse was built in Hebron Center, families in Gilead, Marlborough and Andover complained they had too far to travel to the central meetinghouse. These complaints became political and in 1734, just 17 years after being ordained, the first Congregational Society dismissed Rev. Bliss, who with 20 Hebron families living on the northern end of town declared his following as Anglicans or Episcopalians. This did not solve the problem of where the Congregational Meetinghouse would be located. In 1747 in an effort to “push the issue”, Moses Hutchinson burned the first meetinghouse down. The General Assembly was again called upon to settle the issue of location, but each time the General Assembly Committee staked a new site, Hebron people pulled the stakes up. Finally in 1747, Connecticut’s General Assembly moved to divide Hebron into four ecclesiastical societies, Hebron Center (1st Society), Gilead, Marlborough, and Andover, and recognized the Anglican Church in Hebron. Eventually, Marlborough and Andover would become separate towns, but Gilead did not and remained essentially a farming community with a post office, but few stores.

When in the early 1800’s water powered mills producing cloth and other items developed in Hope Valley, Grayville, and Amston, factory workers created small mill villages close to where they worked. Unfortunately, only Amston with Amston Lake had enough waterpower to expand its mills producing silk. As a result, the Amston mill Village was given a post office, but like Gilead remained part of Hebron.

The primary job of history to solve mysteries. In the case of Hebron, the mystery revolves around the direct relationship of Attawanhood (also known as Joshua), a Sachem of the Mohegan tribe, and son of well-known Mohegan chief Uncas, the Saybrook Legatees, and the original founders of Hebron.

The Mohegan website provides a brief summary of Attawanhood’s father, Chief Uncas. “Uncas, son of Owaneco, was a Pequot chief. His wife was the daughter of Sassacus, Sachem of the Pequots. "Uncas was exceedingly restless and ambitious. Five times, the Indians said, he rebelled against his superior, and each time was expelled from his possessions, and his followers subjected to the sway of the conqueror.” (History of Norwich, Connecticut: From its possession by the Indians to the year 1866, by Frances Manwaring Caulkins)

“Uncas then removed to the interior and placed himself at the head of the Mohegan clans who occupied lands east of the Connecticut river, and west of the great Pequot River now known as the Thames. While Sassacus traded with the Dutch, Uncas developed alliances with the English. War eventually broke out between the English and the Pequot after the murder of John Oldham [from Wethersfield] in 1636 and the punitive expedition by John Endicott. In May of 1637, Uncas with seventy Mohegan warriors joined ninety Englishmen under the command of Capt. John Mason in the famous expedition against the Pequots, sailing down the Connecticut river to Saybrook, then to Narragansett Bay and attacking the Pequots from the eastward. In a series of bloody battles, Uncas and Mason brought the power of the great Pequot nation to an end.”

There is no doubt that Uncas’ decision to support Mason and the new settlers resulted in the ultimate survival of the Mohegan tribe, while the Pequots were virtually wiped out only years after taking on the colonists. It also signaled the start of the permanent settlement of Connecticut as an English colony, usually attributed to Thomas Hooker. The famous Puritan minister, leading a group of 100 settlers, arrived in the Hartford area in 1636, and joined forces with the two existing settlements, Windsor (established in late1633) and Wethersfield (established in 1634.) With Hooker’s arrival, the three settlements set up a “collective government” and soon adopted their “Fundamental Orders” – clearly a constitutional document deemed the first of its kind for guaranteeing individual rights.

It’s not as though peace with the Native American tribes was a given in the mid-17th century; indeed, some tribes began fighting among themselves, and in 1643, Uncas and his Mohegans faced the Narragansetts in battle, with Uncas easily winning. It was about this time that Uncas and his sons, Owaneco and Attawanhood, began a series of land transfers and grants to English settlers who had helped them throughout the tumultuous period.

In 1659, Uncas and his sons, according to the deed filed in Norwich on August 20, 1663, “bargained, sold and passed over, and doe by these presents, bargain, sell and pass over unto the Towne and Inhabitants of Norwich, nine miles square of lands…with all ponds, rivers, woods, quarries, mines with all Royalties, privileges and appurtenances thereunto belonging to them the sayd Inhabitants of Norwich, their heirs and successors forever…” It’s highly doubtful that the Mohegans wrote such language, the basis of which can be found in English law, and according to Forrest Morgan’s 1904 edition of Connecticut as a Colony and as a State, Uncas sold this land in order to fund his ongoing conflict with the Narragansetts.

In 1675, King Philip’s War broke out, causing great damage and loss of life throughout New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. It has been described repeatedly as the “bloodiest and most costly war in colonial history,” and should not be confused with the “French and Indian War” of 1754-1763.

Towns throughout Massachusetts, Connecticut and even Rhode Island were being established at a rapid rate, and Native Americans were increasingly concerned about encroachment on their territories. Prior to King Philip’s War (named after the chief of the Wampanoag tribe, Metacomet, known as “King Philip” by the colonists), interactions were often tense, but generally peaceful. But the colonists of what is now southern and eastern New England were soon viewed by some tribes as a threatening presence, especially as their small population grew at a rapid rate over time and the number of settlements increased almost monthly. Metacomet decided to take on the settler’s encroachment challenge, but again with disastrous results.

While most of the fighting occurred in Massachusetts, Suffield, CT was also attacked, and Providence, the capital of Rhode Island, was abandoned by colonists and burned to the ground by the Wampanoags, who by that time been joined by other, smaller Native American tribes. Uncas was now too old to fight in King Philip’s War, but, according to Mohegan history, “Owaneco, with several hundred Mohegans, rendered valuable assistance to the colonists in their fight against the unfriendly Indians. Attawanhood (Joshua), another son, with a band of thirty Indians scoured the woods in the route of the retreating foe, and took active part in the conflict.”

On February 29, 1676, shortly after the “Great Swamp Fight” of December 15, 1675 (in which the combined forces of colonists and Mohegans successfully destroyed a Narragansett fort in Kingston, Rhode Island) and shortly before his death in May of that same year, Attawanhood issued his “Last Will and Testament.” Because the entire conflict had begun over land rights, it is significant to note that this son of Uncas legally granted a significant amount of land to the colonists.

The document begins “I Joshua Sachim Son of Uncau Sachim Living nigh Eigh tmile Island on the River of Connecticut and within Bounds of Lyme being Sick of Body but of good and perfect memory and not knowing how soon I may depart this Life…” There follows an extremely complicated and confusing description of the lands being given over to a group of men later referred to as the “Saybrook Legatees.” Key names listed in Attawanhood’s will – in terms of Hebron’s ultimate future – were John Talcott, John Pratt, John Chapman, Abraham Post, and Edward Shipman. In the second paragraph of his will, Attawanhood specifically stated: “To Francis Busnell Son & Edward Shipman Son and Mr. John Westall to Every and each of them Three thousand acres…””

In May 1684, Connecticut Governor Robert Treat “conceded that neither he nor [John] Talcott could positively Assert or determine anything concerning the true bounds of said country.” Part of the problem, then and now, was the use of Native American boundary descriptions that consisted of “strange names of places unknown to us.” Yet despite some confusion over the exact boundaries of the land grants, the area now known as “Hebron” was considered by all to be part of the lands granted in Attawanhood’s will.

One of the state’s most famous historians, Benjamin Trumbull, was born in Hebron in 1735 and graduated from Yale University in 1759 with a degree in theology. Trumbull published the first volume of his Complete History of Connecticut in 1797. His recount of Hebron’s settlement provides further insight into our town’s origins:

“Upon the petition of John Pratt, Robert Chapman, John Clark, and Stephen Post, [the governor and council] appointed a committee in behalf of the legatees of Joshua Uncas [i.e., Attawanhood], the assembly granted a township which they named Hebron. The settlement of the town began in June, 1704. The first people who made settlements in the town were William Shipman, Timothy Phelps, Samuel Filer, Caleb Jones, Stephen Post, Jacob Root, Samuel Curtis, Edward Sawyer, Joseph Youngs, and Benoni Trumbull. They were from Windsor, Saybrook, Long-Island, and Northampton. The settlement, at first, went on but slowly; partly, by reason of opposition made by Mason and the Mohegans, and partly, by reason of the extensive tracts claimed by proprietors, who made no settlements. Several acts of the assembly were made, and committees appointed to encourage and assist the planters. By these means they so increased in numbers and wealth that in about six or seven years they were enabled to erect a meeting-house and settle a minister among them.”

Martha Crow (Phelps) was born in Windsor Connecticut in 1670. On November 4th, 1686 she married Timothy Phelps. Initially the Phelps family lived in Windsor, but by 1704, Timothy Phelps had purchased land in Hebron and began to establish a farm in the frontier wilderness of Hebron. In 1704, England was at War with the French and Native Americans in Canada in a conflict known as Queen Anne’s War. Devastating Raids like the one at Deerfield in 1704 put frontier settlements in jeopardy. As a result, the Connecticut Assembly forbade anyone settled on the frontier from leaving, so as not to abandon the British claim to the land. At that time both Timothy Phelps and William Shipman were clearing land for their farms in Hebron, a brave thing to do with a war going on. In 1706 Martha Crow Phelps set out with her children Martha age 16, Timothy age 14, Noah age 12, Cornelius age 8, Charles age 6, and baby Ashbel age 2 to meet her husband in Hebron. They family followed Native American trails and blazed paths, but lost their way as night was approaching. Fearing an attack from wolves or other wild animals, Martha Crow Phelps and her children sought shelter at Prophets Rock on Burrows Hill. They could hear the sound of ax, but could not place where it was coming from. By yelling at the top of their lungs, they were able to attract the attention of Mr. Timothy Phelps and his neighbor William Shipman who following the commotion in the wilderness found Martha Crow Phelps and children. The Phelps family was one of Hebron’s first settled families and lived along Church Street by the Church of the Holy Family. Timothy Phelps died in 1729 at age 65, but his wife Martha Crow Phelps lived to be 105, dying in 1775, the year the first shots of the American Revolution were heard.

Obadiah Horsford was one of the first settlers of Hebron. He purchased land and built his house around 1714 where RHAM Junior and Senior High Schools are located. Obadiah Horsford was a physician, but mainly a farmer. He was also interested in town affairs. Since Church and State were tied together by colonial law (and would be until 1818) setting up a Congregational Church was a high priority with early settlers. Hebron’s first minister Rev. John Bliss became minister of his Hebron Congregation in 1716. A meetinghouse was started in 1714, but not completed until 1720 due to discussions over where it should be located. At various points during that time, Dr. Horsford’s barn was used for services. Obadiah Horsford was captain of Hebron’s militia. Men between 16 and 60 were required to train and serve as soldiers to protect their town across the colony of Connecticut. In the 1720’s Obadiah Horsford gave the land along with his neighbor John Mann for a burying ground along what is now Wall Street.

Cesar Peters was purchased as a young boy of 8 to 10 years old by the Widow Mary Peters. It is not known if Cesar was his original name, but it was the name he was known by in Hebron. He grew up enslaved on the Peters farm located next to Burnt Hill Park. Cesar Peters made a real impression upon people who knew him. He worked hard and was quick to learn farm skills and how to read. He so impressed his owner that on several occasions she said she would free Cesar Peters when he was older. Unfortunately, as Mary Peters’ children grew up and married, Cesar Peters thought he would do the same. He married an enslaved woman named Lois which greatly angered Mary Peters. She threatened to sell Cesar and did – to her son the Rev. Samuel Peters, minister of Saint Peters Church in Hebron and the Anglican Church in Hartford. Rev Peters had returned a few years earlier from being ordained in the Anglican Church in Great Britain. With his salary from his two parishes, Rev. Peters started to buy up neighbors’ farms to create a modest New England Plantation. This allowed Cesar Peters family to live separately from his owner. Another enslaved family headed by Pomp Mundo had a similar living arrangement.

As an Anglican minister, Rev. Peters was required to offer prayers for the English royal family every Sunday. As the events leading up to the American Revolution unfolded, this put Rev. Peters at odds with the Sons of Liberty and Connecticut’s Governor Trumbull. Thus, Cesar Peters’ life became linked with that of his owner Rev. Peters. After the infamous Boston Tea Party, Boston harbor was closed until the English East India Company was reimbursed for the destroyed tea. Governor Trumbull asked that Connecticut towns hold meetings to supply food to the people of Boston. Hebron had the first meeting in the colony. Rev. Peters made such a strong point that the tea was private property and needed to be paid for legally, that Hebron citizens voted not to send any aid to Boston. Hartford held the next town meeting and again Rev. Peters persuaded the citizens not to support Governor Trumbull. This enraged the Sons of Liberty who marched to Hebron and terrorized Rev Peters to the point that in the fall of 1774, long before the first shots were fired at Lexington and Concord, Rev. Peters abandoned his holding of 600 acres in Hebron with seven houses, as well as his slaves, and fled to England. Eventually during the Revolutionary War, the new State of Connecticut would confiscate and rent out Rev. Peters’ plantation, but did not free his slaves, but evicted them. By the end of the Revolutionary War, Cesar Peters’ family found housing in an abandoned blacksmith shop at Burnt Hill Park.

Around 1786, Rev. Peters’ nephew Nathaniel Mann traveled to Great Britain to finish his medical education and visited his Uncle Rev. Peters in London. Nathaniel Mann convinced Rev. Peters to finance a merchant business that would operate out of New York City, but at the last moment was switched to Hebron. The merchant business soon failed and Rev. Peters’ creditors hounded him for repayment. In turn, Nathaniel Mann could not repay his uncle, but with his uncle’s power of attorney, Nathaniel Mann decided to sell off Cesar Peters’ family to settle his debt. On September 27, 1787, Nathaniel Mann brandishing a sword with a party of about 10 men arrived at dusk at Cesar Peters’ house. They bound the family, but one of Cesar Peters’ sons escaped and the women of Burnt Hill tried to forestall the abduction. Patience Graves was threatened at sword point to desist. When the Burnt Hill men returned from militia practice, they were enlisted to help save Cesar Peters’ family which they did. Elijah Graves, Patience Graves’ husband drew up an unpaid bill for clothing he was working on for Cesar Peters, but for which he had not been paid. Hebron’s Selectmen were enlisted to ride to Norwich to bring Cesar Peters’ family back as payment for the clothing bill. The Selectmen were successful and Cesar Peters’ family was placed under the protected custody of Elijah Graves for two years.

In 1789 several Burnt Hill neighbors lobbied the Connecticut General Assembly with testimonies about Cesar Peters’ character and were successful in having Cesar Peters’ family and Pomp Mundo emancipated. With the help of local Hebron lawyers, Cesar Peters then attempted to sue his abductors for damages, but withdrew the case at the last moment and moved out of town. Living in Colchester, Coventry and Tolland, Cesar Peters and his sons worked hard to save money. When his wife Lois died, Cesar Peters married a widow named Sim and added her children to his.

In 1806, Cesar Peters had saved enough money to purchase the two-story Mann House where Nathaniel Mann had grown up with $186 in cash. The property consisted of a two-story house, a barn and two acres of land. Cesar peters found ready employment as a skilled African-American farmer working for gentlemen farmers living in the developing Hebron Center. Cesar Peters died on July 4th, 1814 owning his own home site and solvent with an inventory much like his middling income neighbors. Listed in his inventory is a set of chairs, 8 wine glasses, tea equipment, and a set of china. His descendants would benefit from his success by providing skilled farm labor to Hebron’s center village elites and assuming a middleclass life style. From slavery to success, Cesar Peters’ narrative bears testimony to a story much different from that of African Americans in the South after emancipation.

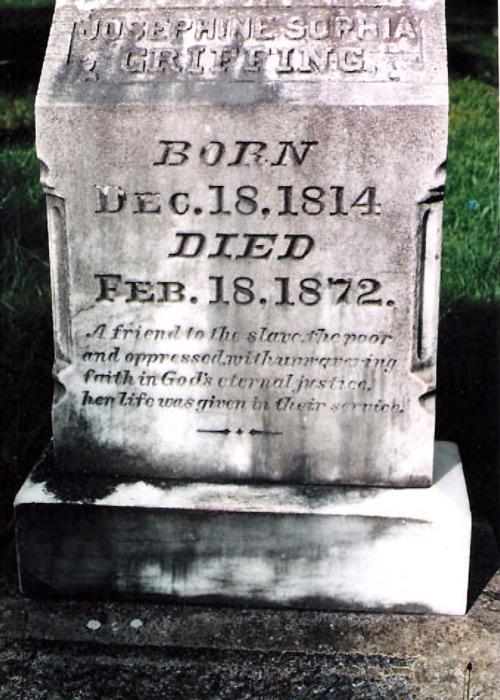

Josephine Griffing's Gravestone in Hebron Born in Hebron in 1814, Josephine (White) Griffing was educated at Burrows Hill School and Bacon Academy. She married Charles Griffing in 1835 and then left Hebron in 1842 for Litchfield, Ohio.

Josephine soon became a sought-after speaker for Abolition as well as Women’s Rights. Her lectures and writing brought her to national prominence.

In Washington, D.C. after the Civil War, she helped found the Freedmen’s Bureau, an organization to help newly-freed slaves acquire the skills they would need to survive in the post-war economy. She received backing from President Lincoln and Secretary of War Stanton in a bid to become first commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Ironically, however, the job was given to a man.

She worked tirelessly over the remainder of her life and helped find northern homes for more than 7,500 freed people. She also helped establish two industrial schools to help train destitute and unskilled women in a trade. Upon her death in 1872, her body was returned to Hebron’s Burrows Hill Cemetery. She was perhaps the bravest crusader ever to be born in our community.

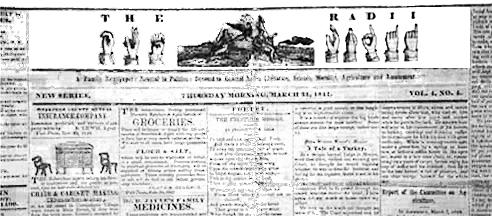

— Levi Strong Backus (June 23, 1803 - March 17, 1869) was born in Hebron, Connecticut the eldest son of Jebez Backus (1777-1855), a tanner and saddle maker in Bolton, Connecticut, who married Octa[via] Strong (1783-1816) in 1801. He was named for his grandfather, Levi Strong (1762-1823). He was apparently born deaf, likely a genetic defect, since his sister Lucy Ann who died at five months of age in 1808, was also deaf.2 He attended the Hartford Academy for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, and after graduation, became a teacher in the Central Asylum School for the Deaf and Dumb (est. 1823) in the hamlet of Buel, just outside the village of Canajoharie, New York.3 He married one of his former students, Anna Raymond Ormsby,4 in the same year that the village of Canajoharie was incorporated (1829). The village "is situated at the confluence of Bowman's creek with the Mohawk and on the Erie canal 55 miles from Albany. It consists of about 100 houses, a Lutheran church, and an academy."5 The school itself closed in 1836, and Levi Backus saw that his 33 students were transferred to the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb in New York City.6 That winter Backus organized a newspaper devoted to the deaf community called the Radii (later the The Canajoharie Radii and Taxpayer's Journal). A catalogue of newspapers published in 1884 has this entry: "1837. — The Radii, at Canajoharie, by Levi S. Backus a deaf mute. In 1840 removed to Fort Plain, and in 1856 to Madison County. Subsequently returned to Canajoharie. Still published."7 Backus applied to get the Radii distributed free of cost to the members of the deaf community throughout New York state.8 In 1844 he was able to use the state subsidy to mail the Radii to deaf people across the state.9 The original Canajoharie site of the paper fell victim to the fire of 1840, the same year that saw the publication of the present book.10 Backus was the first person in America to insert pictures of the hand signs for the deaf in a newspaper's masthead.

Because of his association with deafness, Backus was particularly interested in non-verbal communication by means of signs. In later years he became a book publisher for other authors, printing a book on grammar (1858) and another of poetry (1861). He died in Montgomery, New York, in 1869, survived by his widow.