The Hebron Historical Society

Hebron, Connecticut

Enjoy Hebron - It's Here To Stay ™

Enjoy Hebron - It's Here To Stay ™

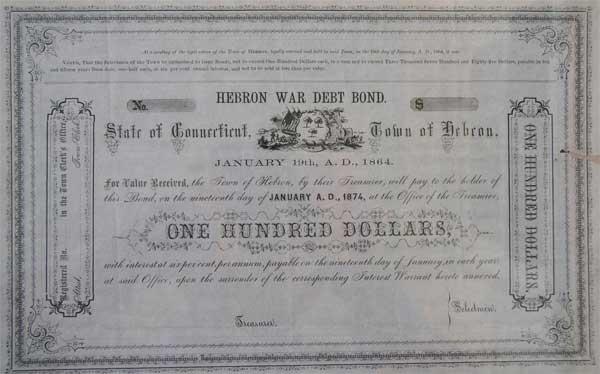

On January 18, 1864, a Hebron Town Meeting was held, and residents voted to issue Civil War Bonds to "support our troops." A notice for a Town Meeting was published on January 11, 1864, Item 3 being: "To see if the Town will raise a tax to defray the expenses of paying the drafted men" to fill the Quota of Said Town under the last call of the President.

The Smith family name has been well known in Hebron for two centuries, going back to 1794 when Nathan Smith purchased land from Increase Porter. That homestead, which is still in the family today, has housed generations of Smiths, members of which have carefully documented not only their genealogical lines but also the historical events that have shaped and influenced both their family and their town.

Many residents today still remember Edward Ashley Smith, and his wife, Annie Palmer, and their large farm which produced dairy products, eggs and apples. Ed and Annie married in 1918, and a few years later, they purchased the Phelps/Waldo farm across the road from the Smith homestead. It was here that their three children, Bradford Edward, Edwin Richardson, and Marie Purington, were raised. The beautiful four-pillared house, built around 1852, remains one of Hebron’s most unique historical homes.

The Smiths’ firstborn, Bradford, was born in 1919, and attended Hebron’s Center School (now the American Legion/VFW). Like most of his peers, he attended Willimantic High School and graduated in 1937. His parents, keen on education, encouraged their children to learn and study, despite the daily demands of the farming operation. It was no surprise that Brad went on to Yale after high school, earning a Bachelor’s degree in Industrial Administration in 1941. During that time, he was also a 4-year member of the ROTC.

We know much of what happened to this young Hebron resident as a direct result of his lifelong love of genealogy and history. Recently, Brad’s son, Edward, who now lives in Glastonbury, provided the Society with a vast number of documents written by his father. One in particular, “Military History of Bradford E. Smith 1941-1945,” provides wonderful insight into Brad’s years following his graduation from Yale. This document was ultimately submitted to Dr. Stephen Ambrose, and is now included in the collection of World War II memories at the Eisenhower Center in Abilene, Kansas.

War, of course, had already broken out in Europe, so it came as no surprise when he was called for active duty on August 28, 1941. Off he went to Fort Sill, Oklahoma as a commissioned Second Lieutenant, returning briefly to Connecticut on December 3, 1941, where he married his longtime sweetheart, Lois Helen Goulett, at her home in West Haven. The young couple honeymooned while making the long drive to Brad’s next military assignment at Fort Knox, Kentucky.

They arrived at the base on December 7, the same day that the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. While concerned with this change in the war effort, and its implications for American servicemen, the young couple had other things on their minds, such as finding a place to live. “The news of the attack on Pearl Harbor was coming over the airways…[but] we were concerned with finding a place to live that night. We finally left our friends, went to Elizabethtown, went into the local drug store and luckily the druggist knew of a place for us to live.”

Brad’s division, the 5th Armored, was transferred in February 1942 to Camp Cooke, California, where he and Lois lived in a motel while Brad underwent intensive training, including one month in the Mohave Desert. The entire unit of the 58th Armored F.A. Battalion, which included Brad’s division, was then alerted for overseas duty, and Brad, now a First Lieutenant, and the men were transferred in August by Pullman-car train cross country to Camp A.P. Hill, Virginia.

In November, Brad left for Camp Kilmer, New Jersey where he was scheduled to ship out to the African theatre, and Lois returned to her parent’s home in West Haven. She was to stay there for nearly three years, bearing and raising their first son, Edward, while her husband was overseas.

“By November 1st 1942 we were loaded on a ship near New Brunswick, New Jersey, the Santa Rosa, bound for Casablanca. Then followed some 18 days rolling on the ocean. The ship rolled and rolled. We learned to our amazement that the ship could roll 55 degrees off the vertical and still right itself. Men could not stay on their feet in the mess hall, and that soon became a real mess.”

Brad’s first “base” was in Casablanca, where his duties were varied… and fascinating. “When FDR (Franklin Delano Roosevelt) came to Marrakech, we had to post guards every few hundred feet, all the way from Casablanca to Marrakech. This was the famous meeting of FDR and Churchill.” His first combat mission, occurring just two days after he was promoted to Captain, was in Maknassy, where, on March 22, 1943, “we held the west flank of Rommel’s forces while they retreated northward past us and other allied troops.” Brad documents the scarcity of arms, many of which were malfunctioning due to the never-ending sand storms.

There was a short period of “peaceful life” after the German forces surrendered in Tunisia, but the young Captain was soon transferred to Sicily. “At first there was no opposition, and hordes of Italian soldiers came to us with hands in the air and waving white flags of surrender. We couldn’t be bothered with them and simply waved them on to the rear echelons where the units in charge of PWs could take care of them.” After a few more skirmishes, the Italian theatre was declared over, and Brad’s battalion was notified that they would soon be on their way to England to join the operations there. His time in England was “relaxes and peaceful.”

“Eventually dances were arranged for the enlisted men and others for the officers…The local people were most hospitable. On a more serious note, several talks were given to other service units about our experiences in Africa and Sicily. Hopefully our experiences were helpful to them who had not yet experienced combat... [We even took a] trip to London for a few days of schooling. This permitted us to see the sights of London, including some plays, Madame Tousseau’s Wax Works, and St. Paul’s Cathedral. A trip to nearby Oxford gave us a brief look at the university there. But all good things must come to an end…” The battalion was given orders to move on to France, where they faced the one of the biggest challenges of World War II. The largest ir, land, and sea operation ever undertaken, before or since that time, included 5,000 ships, 11,000 airplanes, and almost 200,000 Allied personnel against Hitler’s forces on the beaches of Normandy.

Brad’s detailed memories that fateful day is harrowing. “D-Day was scheduled for June 5, 1944... However, the invasion was canceled the first day and we all turned around and went back into the harbor and sat on the ships. But the next day we started again and this time it was for real… The beach was so covered with dust and smoke, it was almost impossible to see where our shells were landing, but we did the best we could.” At its appointed time to head into the beach, his ship was hit almost immediately by a mine, rendering it inoperable. The delay may have saved his life. More than 4,000 Allied forces died that fateful day in history, and Brad witnessed many of his friends counted among those deaths.

Brad faithfully recorded the daily events of the war, from June 6 through November 2, 1944, noting in his document that those details were “taken extensively from my notes taken at that time and recorded in a Transit Notebook.” On September 29, in the middle of this hell, and as his battalion moved into Germany, he was promoted to Major. Young Bradford Smith of Hebron, Connecticut, was barely 25 years old.

At that point, Major Smith was transferred: “The second unit that I served with in the European Theater of operations was the 406 Field Artillery Group, from Nov. 24, 1944 to June 1945.” The war was winding down, and his role then supported the Occupational Forces, although seeing the Russians arrive in jeeps was concerting.

It was time to go home. “In typical Army fashion there was a point system to determine who had priority on getting home. You were awarded points for each campaign you served in, for a wife, for a child. Being a veteran of Africa and Sicily, as well as Europe, I had many more points than anyone else in the 406th…” After a long flight from Casablanca to Miami, Florida (via Morocco, Dakar, and Brazil), Brad boarded a train, finally heading back to Connecticut.

“While waiting on the platform a conversation with one of he officials of the New York New Haven and Hartford Railroad brought out the information that my wife lived in West Haven, and that her father, Paul R. Goulett, was a vice-president of the Railroad. e then made things happen. He called the Gouletts and got instructions to get his car and bring me out to 175 Church St., West Haven. So I arrived to be greeted by my wife, our son Edward, and Mr. and Mrs. Goulett after an absence of 33 months.”

Welcome home, Brad. Welcome home to all the valiant men and women who have served our country so well in times of war.

“At the time [I enlisted] I was working at Electric Boat in Groton as a ship fitters helper. When I informed the boss, I was told I could get a deferment because it was a defense-related job. But at that time, a civilian at my age was looked down upon if he wasn’t in the services. Besides, all my friends were going in, so I went too.”

Thus begins the memories of Leonard Carey Porter, one of Clarence and Alma Porter’s four sons, all of whom enlisted in the service of the United States during World War II. (The other Porter brothers were David, who served in the Pacific theatre with the Navy; Earl, a Marine who served in the Marshall Islands; and Howard, who served with the Army Air Corps in England.)

There are actually two versions of Lenny’s story. An earlier, 35-page typed version of the document was recently donated to the Hebron Historical Society by Donald Robinson’s family. Lenny notes in this version that he had recorded his memories at the request of his daughter-in-law, Nancy Porter, and that it had been written 38 years after his discharge, which would have been approximately 1984. The second version, a 71-page, handwritten document, is dated April 5, 2004, and was recently loaned to the Historical Society by the Porter family. While similar, both versions offer unique details.

Lenny’s recollections of his basic training in Texas are sure to bring laughter. “We didn’t have a chow car on the train, so twice a day it would stop in some town and we would be fed. This must have been prearranged because they were ready for us. They all looked like lunch wagons and all loaded with cockroaches, some big enough to be waiters.” Lenny also recounts the servicemen forming tight circles after calisthenics, trying to catch jackrabbits. “We would grab a leg, then they would start kicking and it seemed they could kick harder than a jackass. I never did see one caught. What fun.”

Lenny readily volunteered for flight duty, and was moved to Tucson, Arizona for B-24 flight training. It was in Tucson that approximately 30 flight crews were formed, and after listing each individual man in his particular crew, Lenny, the Flight Engineer, notes: “These are the guys I would go into combat with.”

Training day and night, the crews were sometimes so exhausted they would simply hang their flight gear on the ends of their bunk beds, ready for the next flying session. “During that time, we started to lose some or crews. That’s always a morale buster,” Lenny wrote. From Tucson, the crews were sent to Salinas, California for Phase Two training. Here, more crews were lost and even Lenny’s crew suffered a close call, almost crashing into the Cascade Mountains. “The Good Lord was with us,” he wrote.

But accidents continued to happen. “As we finished up our 2nd phase of training, we had lost almost half of our crews. This had everyone on edge and it was tough to cope with.” The Army decided to send the crews to Blythe, California for two extra months of training. “In my opinion that extra training time had a lot to do with our survival in combat.” But even in Blythe, another crew was lost. Lenny witnessed the horrific accident. “They were really struggling to stay in the air. Suddenly, the wing dropped down and the nose too and they went right into the ground. There was lots of dust, then a huge ball of fire as the fuel tanks ruptured and caught fire. No survivors.”

In such a stressful environment, Lenny was especially happy to learn that his old friend, Joe Kowalski, was stationed in Yuma, Arizona. Lenny and Joe had been classmates at Hebron Center School, and Lenny wanted to see him. He obtained a pass and set out on foot for Yuma, battling rattlesnakes and sleeping on the ground until he finally was able to hitch a ride with an Army convoy. Lenny and Joe visited for a couple of hours; Lenny then returned to Blythe, hitching a ride with the same convoy.

It was time to go to war. Lenny’s crew named their plane “Slow Time Sally.” Leaving from Bangor, Maine, “Sally” flew over key stop points until they reached their ultimate destination of Benghazi, Libya. “In this area the fighting went back and forth between the Germans and Italians and the British. The whole area was just one big junk yard…The ground was just littered with burned out tanks, shot up vehicles of all sorts. What a mess of iron.”

Soon, Lenny’s squadron was moved to Tunisia: “Now, it was time for real combat.” Ordered to strike a bridge in East Italy, vital to the German supply line, the day began at 3:00 a.m., a quick breakfast, a briefing on how much opposition to expect, “and, most importantly, a prayer from our chaplain putting the Good Lord on board with us.” The planes, powered by Pratt & Whitney engines, took off four abreast. P-38 fighter escorts soon surrounded the bulkier B-24’s. The bridge was easily destroyed. “I will say now that of all 50 missions I flew, that first one was by far the easiest. No enemy fighters. No anti-aircraft fire. No bad weather. No nothing. But that would be the last one like that.”

From this point forward, Lenny Porter experienced war first hand, non-stop. He discovered a man’s leg, blown off at the hip, in the sand of a nearby beach. He detonated a live bomb on board his ship that hadn’t released. He saw his friend and fellow gunner, Art “Brownie” Brown, killed. He faced a target in Weiner Neustadt, Austria, surrounded by 400 German anti-aircraft batteries.

On November 2, 1943, the crew moved to Brindisi, Italy, where they were ordered to hit Weiner Neustadt again. “That news got me shaking in my shoes but you couldn’t say, well I don’t think I will fly today. We all knew what was coming.” German MiG 109’s were soon right above Lenny’s squadron. “They would come at full throttle and dive right through the formation. It happens so fast…” Yet the mission was successful this time. “That place was just one big heap of junk.”Shortly after Christmas, Lenny’s plane suffered severe damage from German flak. The Number Four engine caught fire; “then the No. 3 engine caught fire. Now we are in deep trouble.” Chaos broke out on the plane; Lenny had a gunner hold on to him so he wouldn’t fall out of the plane as he did repairs. He pumped fuel from one cell to another, trying to stabilize the plane, then starting throwing out anything of weight. Eventually, an emergency landing was made in friendly territory, but “Slow Time Sally” was so shot up, it never saw action again. Lenny, for his part, was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, “awarded to any officer or enlisted man of the Armed Forces of the United States who shall have distinguished himself in actual combat in support of operations by heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in an aerial flight.”

Following many more heart-stopping engagements, including one over Munich, Lenny finally came home in 1944. He was happy to be back in Hebron, although he still faced the realities of America in wartime. “Since the war was still on, the Rationing Board was operating. It was run by Mrs. Getchell who lives on the corner of 66 and 316. I had my car and I was always after gas stamps. One day when I went to see her, she said to me, ‘Leonard, don’t you know there is a war going on?’ As if I didn’t know about the war.”

Less than a month after finishing his memoirs, just after his 87th birthday, Leonard Carey Porter passed away on May 1, 2004. What a gift he has left us by documenting his memories.